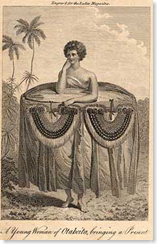

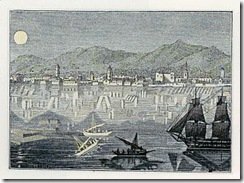

Around 1,000 years after Tahiti was first settled by Polynesians, the English sailor Samuel Wallis arrived to claim the territory as ‘King George the Third’s Island‘. The Tahitians attempted to repulse the intruders, but the superior weaponry of the English made an unequal match. When the French explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville arrived the following year, in 1768, he was given a much friendlier reception. In response, he claimed the territory for France as ‘New Cythera’. In his 1771 publication, Voyage autour du monde, Bougainville depicted the island as an earthly paradise, far from the corruption of civilisation.

Bougainville’s report had a strong effect on the French enlightenment, inspiring the utopianism of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In his Supplément au voyage de Bougainville, Denis Diderot uses the Tahitian figure Ohou as a foil for critiquing Western civilisation. Ohou explains the readiness of Tahitian men to share their womenfolk with the Europeans as a long-term strategy to appropriate all the best of their civilisation into their own culture. Diderot reflects, ‘Savage life is so simple and our societies are such complicated mechanisms. The Tahitien is near the origin of the world, the European near its old age.’ While the idea of South as a child is often presented negatively, particularly in a developmental paradigm, in this case it indicates an innocence with more future than the jaded Old World.

Bougainville’s report had a strong effect on the French enlightenment, inspiring the utopianism of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In his Supplément au voyage de Bougainville, Denis Diderot uses the Tahitian figure Ohou as a foil for critiquing Western civilisation. Ohou explains the readiness of Tahitian men to share their womenfolk with the Europeans as a long-term strategy to appropriate all the best of their civilisation into their own culture. Diderot reflects, ‘Savage life is so simple and our societies are such complicated mechanisms. The Tahitien is near the origin of the world, the European near its old age.’ While the idea of South as a child is often presented negatively, particularly in a developmental paradigm, in this case it indicates an innocence with more future than the jaded Old World.

Following two visits by James Cook, Tahiti was chosen by the English as a source of breadfruit to be used as cheap food for slaves in the West Indies. In 1789, the captain of the ship commissioned for this purpose was deposed by rebellious sailors who turned their backs on civilisation and resigned themselves to die in the antipodes. The ‘mutiny on the bounty’ reflects the conflict in expanding English empire between the force of order located in the cold dark North and the temptations that seemed on offer in the warm verdant South.

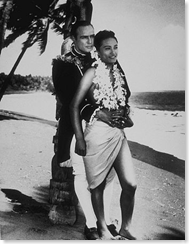

The spirit of Fletcher Christian continues. While playing the rebel in the 1961 film version, Marlon Brando turned his back on America, married his Tahitian lead and purchased the island first chosen by Bligh’s deserters as an escape. This came to a violent denouement when his first son called Christian murdered his Tahitian daughter’s native husband. The real Fletcher Christian’s men settled on Pitcairn Island, burnt the Bounty, and created an English-Tahitian hybrid micro-society, which is still alive today in Norfolk Island. As is usual, the only news coming from this world is of sexual abuse and murder. We hear little of the thriving artistic and literary life on the islands.

The spirit of Fletcher Christian continues. While playing the rebel in the 1961 film version, Marlon Brando turned his back on America, married his Tahitian lead and purchased the island first chosen by Bligh’s deserters as an escape. This came to a violent denouement when his first son called Christian murdered his Tahitian daughter’s native husband. The real Fletcher Christian’s men settled on Pitcairn Island, burnt the Bounty, and created an English-Tahitian hybrid micro-society, which is still alive today in Norfolk Island. As is usual, the only news coming from this world is of sexual abuse and murder. We hear little of the thriving artistic and literary life on the islands.

| Norfolk Island fibre artist Margarita Sampson ‘Welcome/Greetings’ (2006) recycled books & ink. 6ft x4 ft wide. Photo: Alex Kovoskali, shown at Craft Victoria along with Dar Plait fe Ucklun Norfolk Island Weaving for Common Goods. |  |

Bounty Chocolate Bar, produced by Mars, used the idyllic image of the Pacific island as a fantasy for consumers to indulge while eating a ‘taste of paradise’.

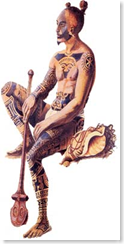

One enduring legacy of these first visits is the tattoo. In a society without capital, the tattoo was a principle means by which power and status could be acquired. All it needed was the capacity of the individual to endure great pain. After recovering from the ordeal, proof of their strength was available for all to see. The European sailors who acquired tattoos for themselves then introduced this skin economy into the West, where it still flourishes today, particularly among those who do not have access to other forms of capital. The tattoo is one of the most visible ways in which the South has imprinted itself on the rest of the world.

One enduring legacy of these first visits is the tattoo. In a society without capital, the tattoo was a principle means by which power and status could be acquired. All it needed was the capacity of the individual to endure great pain. After recovering from the ordeal, proof of their strength was available for all to see. The European sailors who acquired tattoos for themselves then introduced this skin economy into the West, where it still flourishes today, particularly among those who do not have access to other forms of capital. The tattoo is one of the most visible ways in which the South has imprinted itself on the rest of the world.

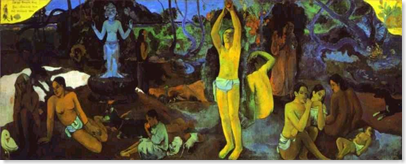

In 1842, Queen Pomare signed a treaty that made Tahiti a French Protectorate. Etablissements français d’Oceanie became a space for artists to position themselves against the conventional order. In 1891, Paul Gauguin arrived in Tahiti seeking escape from the modern world. Having grown up in Peru, Gauguin shared with van Gogh a love of ‘primitive cultures’ such as the Brittany peasant. His journal Noa Noa documents Gauguin’s journey away from civilisation into the full life of nature. After joining vigorous work with natives, Gauguin can finally claim to be one of them:

This cruel assault was the supreme farewell to civilization, to evil. This last evidence of the depraved instincts which sleep at the bottom of all decadent souls, by very contrast exalted the healthy simplicity of the life at which I had already made a beginning into a feeling of inexpressible happiness. By the trial within my soul mastery had been won. Avidly I inhaled the splendid purity of the light. I was, indeed, a new man; from now on I was a true savage, a real Maori.

Gauguin’s paintings have become a universal symbol of Tahiti as a world of classical beauty. This has become ever more commodified through tourism and consumerism. In 1913, the first postage stamp from this region contained a dusky beauty with a hibiscus flower behind her ear. It was only a matter of time before Club Med set up shop.

Gauguin’s paintings have become a universal symbol of Tahiti as a world of classical beauty. This has become ever more commodified through tourism and consumerism. In 1913, the first postage stamp from this region contained a dusky beauty with a hibiscus flower behind her ear. It was only a matter of time before Club Med set up shop.

In 1963, as France anticipated Algerian independence, Charles de Gaulle chose the Pacific territories as the new site for nuclear testing. The assumption was that the atolls and their surrounding waters were empty. Tensions rose during the course of atomic explosions on Moruroa. In 1977, the Polynesian Liberation Front was formed by Oscar Temaru, who is now president of the local parliament. In 1992, during the ‘day of the waters’, PLF leaders gathered in Salzburg to articulate their position. Myron Mataoa stated, ‘Now this island of Moruroa — you know what Moruroa means? Moruroa means “the land of secret”. The land of secret. And today that land is really a land of secret where we don’t get any information from the French administration on how bad was their testings since 1966.’

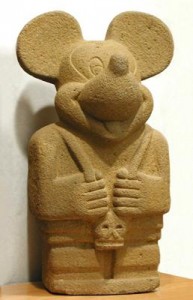

Tourism is a dominant force in contemporary Tahiti. The German-born sculptor Andreas Dettloff has produced a series of work in the mode of ‘reverse primitivism’, depicting forms like shrunken skulls but with Western iconography such as Coca-Cola. One of his most successful series were skulls supposedly of Gauguin. A resident for twenty years, Dettloff’s work is disliked by tourist operators, but enjoyed by native Tahitians.

Gauguin in his last décor (Andreas Dettloff, 2008)

A major force in Tahitian cultural revival was the poet Henri Hiro, who called on his people to recover their lost culture. His called on Tahitians to ‘Eat the time! It is necessary to eat time! You must eat the time lost by your past!’ The Tahitian concept of time and space is opposite to the Western: Tahitians look forward to the past, while their backs are turned to the future. To eat the time is to devour the process of Westernisation that has alienated Tahitians from their culture. Like the Brazilian concept of anthropofagi, it evokes cannibalism as a cultural response to the outside world.

A major force in Tahitian cultural revival was the poet Henri Hiro, who called on his people to recover their lost culture. His called on Tahitians to ‘Eat the time! It is necessary to eat time! You must eat the time lost by your past!’ The Tahitian concept of time and space is opposite to the Western: Tahitians look forward to the past, while their backs are turned to the future. To eat the time is to devour the process of Westernisation that has alienated Tahitians from their culture. Like the Brazilian concept of anthropofagi, it evokes cannibalism as a cultural response to the outside world.

Hiro has been followed by a number of women writers whose writing has been described as a form of ‘ancestral realism’ in which previous generations are considered an active presence in daily life.

From the Western perspective, Tahiti represents the idea of South as a prelapsarian world from which an attack can be mounted on the dominant order. Tahiti was first used by bourgeois French intellectuals to critique the over-civilised Ancien Régime, and continues to be used as a satire on the contemporary global order by those at its periphery.

And where do the Tahitians themselves stand in this. Are they mere extras in cinematic Western fantasies? Recent Tahitian voices seem to revert back to the hostility they showed their first English visitor, Wallis. Perhaps that is the legacy of innocence. Cast as children, Tahitians are positioned beyond the law, without adult forms of exchange. Violence might seem the only way to assert identity. The situation appears similar to the myth of El Dorado in Colombia.

This duality of innocence/violence seems an important dimension to Western ideas of South. It’s interesting to understand its dynamics and whether the same applies to ideas of South from other directions.

References

- Greg Dening Mr Bligh’s Bad Language: Passion, Power and Theatre on Bounty Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992

- Denis Diderot Supplement to the Voyage of Bougainville (1772)

- Rod Edmond Representing The South Pacific: Colonial Discourse From Cook To Gauguin New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997

- Paul Gauguin Noa Noa: The Tahitian Journal (trans. O.F. Theis) New York: Dover, 1985 (orig. 1919)

- Miriam Kahn ‘Tahiti: The Ripples of a Myth on the Shores of the Imagination’ History and Anthropology (2003) 14: 4, pp. 307-326

- Dan Taulapapa McMullin “The fire that devours me’: Tahitian spirituality and activism in the poetry of Henri Hiro’ International Journal of Francophone Studies (2005) 8: 3, pp. 341-357

- Robert Nicole ‘Resisting orientalism: Pacific literature in French’, in (ed. Vilsoni Hereniko, Rob Wilson) Inside Out: Literature, Cultural Politics, and Identity in the New Pacific : Rowman & Littlefield, 1999

- Robert Nicole The Word, The Pen, And The Pistol: Literature And Power In Tahiti Albany: State University of New York Press, 2001

- Tattoo: Bodies, Art and Exchange in the Pacific and the West edited by Nicholas Thomas, Anna Cole and Bronwen Douglas London: Reaktion, 2005

Thanks to Margarita Sampson and Andreas Dettloff.

Colombia emerged as a nation from the Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1810, lead by the forces of Simón Bolívar. The Bolivarian dream of a United States of South America came to a cruel end as the Colombian federation was broken up by reactionary forces in Venezuela and Ecuador. The conflict became a ‘war to the death’ (guerra a muerte) where no prisoners were taken. As Eduardo Galeano comments on Bolivar’s demise: ‘Was this, was this history? All grandeur ends up dwarfed. On the neck of every promise crawls betrayal. Great men become voracious landlords. The sons of America destroy each other. ‘

Colombia emerged as a nation from the Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1810, lead by the forces of Simón Bolívar. The Bolivarian dream of a United States of South America came to a cruel end as the Colombian federation was broken up by reactionary forces in Venezuela and Ecuador. The conflict became a ‘war to the death’ (guerra a muerte) where no prisoners were taken. As Eduardo Galeano comments on Bolivar’s demise: ‘Was this, was this history? All grandeur ends up dwarfed. On the neck of every promise crawls betrayal. Great men become voracious landlords. The sons of America destroy each other. ‘