We began the journey way up in great Arctic landmass of Canada, where the idea of North frames a direction away from the dominant power—a loneliness that brings people together. Now we descend to the opposite end of the world, a little island in the Indian Ocean.

Early ideas of South speculated about an Antipodes that counterbalanced the known world. In this anti-world, the natural order of things would be reversed—day would be night and people would have feet on their heads.

Mauritius has several claims to fame. These are not the usual proud achievements—Nobel Prize winning novelists, the biggest of its kind in the Southern hemisphere, etc. Mauritius’ singular contribution to world history appears to be in its capacity to make mistakes.

The founding myth of philately is the Blue Penny stamp. On 20 September, 1847, a half-blind Mauritian watchmaker Joseph Barnard was charged with engraving plates for the first stamps to be produced outside the British Empire. After a visit to his friend the postmaster, Barnard mistakenly printed ‘Post Office’ rather than ‘Post Paid’. With this moment of absent-mindedness, Barnard had destined this penny stamp to acquire the current value of approximately €1 million Euros. Why should such a mistake be now so valuable? We tend to notice mistakes more than we do clockwork order. To what extend does our confidence in the bureaucratic systems of the north depend on the existence of their exception in the South?

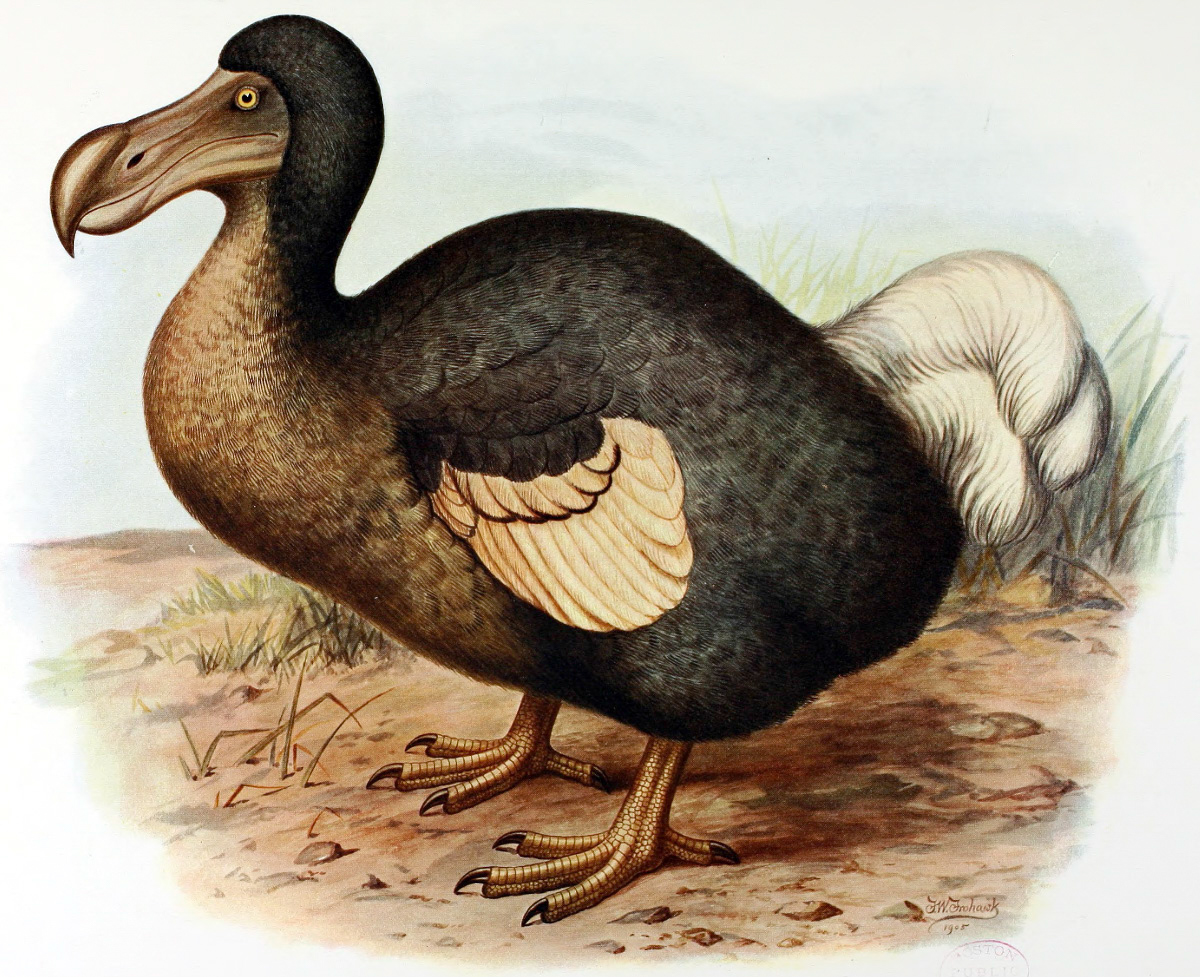

The second claim is the Dodo. Portuguese for ‘simpleton’, the Dodo is a universal figure of ridicule. Though related to the pigeons of Southeast Asia, the Dodo abandoned the power of flight for a lazy life on an island secure from predators. For biologists like David Quammen, the Dodo is a classic moral tale of extinction through isolation: ‘that insular evolution, for all its wondrousness, tends to be a one-way tunnel toward doom.’ To ‘go the way of the Dodo’ is to stupidly cling to weak provincial tradition in the face of a stronger global force. To what extent has colonisation been assisted by the ghosts of South’s flightless birds?

Behind these two clichés of Mauritian errantry lies a complex country. This Francophone island is populated largely by those of Indian descent. Though French speaking, for the past two centuries Mauritius has been a proud member of the British Commonwealth. There is a significant population of Creoles, descended from African slaves. Marginalised from official life, Creole culture developed a rich oral and musical tradition. The Sega is a national dance of Mauritius, which combines European polka with African rhythm. In the 1980s, this evolved into Seggae, by a Mauritian Bob Marley called Kaya, who was allegedly murdered while in police custody.

Behind these two clichés of Mauritian errantry lies a complex country. This Francophone island is populated largely by those of Indian descent. Though French speaking, for the past two centuries Mauritius has been a proud member of the British Commonwealth. There is a significant population of Creoles, descended from African slaves. Marginalised from official life, Creole culture developed a rich oral and musical tradition. The Sega is a national dance of Mauritius, which combines European polka with African rhythm. In the 1980s, this evolved into Seggae, by a Mauritian Bob Marley called Kaya, who was allegedly murdered while in police custody.

Today, Creole plays a prominent role in Mauritian culture. The publishing house Lalit (‘struggle’ in Creole) produces bi-lingual editions. This includes a collection of Creole folk tales such as the ‘Foor Bells’ which explains why diamonds became rare. It has also published the story of Le Morne, about Creole slaves who escaped into the mountains where they lived isolated from colonial settlements. When troops finally appeared, the population collectively leapt from the precipice rather than submit to slavery again. They were wrong. The British soldiers had come to inform them of the abolition of slavery.

As indentured labourers, the original Indians were illiterate, thus had no way of maintaining contact with home. They were predominantly from Bihari, where the river Ganges plays a critical role in cultural calendar. In 1897, a Hindu priest had a vision of a spring containing water from the Ganges. From this grew a legend that Shiva had spilt some drops of the Ganges over the island while on his way to deposit it in India. This lake Ganga Talao is now the site of the biggest annual pilgrimage of Indians outside India. It is home to paris, or nymphs of heaven whose beauty cannot be matched.

Mauritius is a treasury of mistakes. They constitute a wealth of possibility.

Jean-Lewis Dick, the carver was the seventeenth child of a Creole family, born on leap day, like today, 29th February. His mother died in childbirth. For all intents and purposes, he was a mistake. Louis has since used his marginality and built a culture for his Creole neighbours, using whatever resources he has to establish a sculpture school and gallery. Strange how something of great value can emerge from what seems at the time to be a terrible mistake.

Might the same be of the South. Used as a theatre of ridicule to show up the civilised and orderly North, perhaps these mistakes form a treasury of meaning yet to be unpacked.

References

- Sarita Boodhoo ‘Religious and cultural traditions of Biharis in Mauritius’, in (ed. Marina Carter) The Bihari Presence in Mauritius Port Louis: Centre for Research on Indian Ocean Studies, 2000, p. 134

- Roger Moss Le Morne (trans. Lindsey Collen) Port Louis: Ledikasyon pu Traveyer , 2000

- David Quammen The Song of the Dodo: Island Biogeography In The Age Of Extinctions London: Hutchison, 1996, p. 147

- Sirandann Sanpek: Zistwar an Kreol (Baissac’s 1888 collection) Louis: Ledikasyon pu Traveyer, 1997

- Lalit (see particularly Lindsey Collen’s articles on the political issues such as Diego Garcia)

- Mahatma Gandhi Institute the island’s only art school and gallery

- Littératures de l’Océan Indien