‘Africa begins at the Pyrenees.’

Voltaire

“Whatever has black sounds has duende.”

Garcia Lorca

Spain seems an exception to civilised Europe. While the Enlightenment promoted the pursuit of reason based on natural order, Spain remained captive to a theatre of violence as it persecuted heretics and bulls. Is this a true image of Spain?

Spain seems an exception to civilised Europe. While the Enlightenment promoted the pursuit of reason based on natural order, Spain remained captive to a theatre of violence as it persecuted heretics and bulls. Is this a true image of Spain?

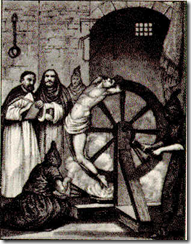

What has been termed the ‘Black Legend’ of Spain emerged during the Reformation, where the Inquisition was depicted by Protestants and Anglo-Saxons as a sign of inherent Spanish cruelty.

The negative view of the Spanish was further elaborated by the French. To their neighbours across the Pyrenees, the Spanish were a barbarous people, tainted by their African influence. They were variously described at Turkish or Arab Christians—anything but European. According to Stendhal, ‘Blood, manners, language, way of living and fighting, everything in Spain is African. If the Spaniard were a Muslim he would be a complete African’.

From 1795, Spain was occupied by Napoleonic France for nearly ten years. After expelling the French, the restored King Ferdinand VII initiated a reaction against liberalism. The resulting French disdain for the Spanish cast an orientalist shadow, popularised in the literary genre of travel writing known as the Espagnolade. The Spanish themselves conspired to construct a romantic image of themselves: the middle class reacted against the Bourbon invaders by inventing a defiant national culture drawn from the Madrid working class, including bull-fighting and flamenco.

From 1795, Spain was occupied by Napoleonic France for nearly ten years. After expelling the French, the restored King Ferdinand VII initiated a reaction against liberalism. The resulting French disdain for the Spanish cast an orientalist shadow, popularised in the literary genre of travel writing known as the Espagnolade. The Spanish themselves conspired to construct a romantic image of themselves: the middle class reacted against the Bourbon invaders by inventing a defiant national culture drawn from the Madrid working class, including bull-fighting and flamenco.

The rest of Europe used Spain as a stage for the grand passions. The Spanish south, in particular Seville, became the setting for the passions of European opera, such as Barber of Seville, Don Giovanni, and Il Travatore. This culminated in Bizet’s Carmen, which orchestrated and choreographed the wild Andalusian spirit. Spanish orientalism continues today in the world music scene, as flamenco is celebrated in the cinema of Carlos Saura and Tony Gatlief.

As with Italy, Spanish culture internalises this division within its own territory. For nearly 800 years, from the early eighth century, the south of Spanish was an Islamic civilisation. In 1492, on the same year that Christopher Columbus set out to find the New World, the new Christian monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella forced the surrender of Granada, the last Muslim city, and expelled the Jewish population from the entire peninsular.

After the Reconquista, those of Moorish background were always under suspicion. The original terms of surrender guaranteed that Moors would keep their goods and continue to observe Sharia. But forced conversions soon followed. Even those who converted became victim of new laws, such as the limpieza de sangre (purity of blood). Granada soon lost its once thriving silk industry and was eventually eclipsed by Seville, which became the gateway to the new world.

After the Reconquista, those of Moorish background were always under suspicion. The original terms of surrender guaranteed that Moors would keep their goods and continue to observe Sharia. But forced conversions soon followed. Even those who converted became victim of new laws, such as the limpieza de sangre (purity of blood). Granada soon lost its once thriving silk industry and was eventually eclipsed by Seville, which became the gateway to the new world.

After having brutally expelled the heretics, signs of regret began to appear. This ambivalence is particularly strong in the classic novel of Spanish literature, Don Quixote. The story of the knight-errant and his squire takes the form of a journey south, from Castile and towards Seville. In the course of his adventures, Quixote feels free to identify any untrustworthy character as an Andalusian moor. However, in attempting to revive the earlier romances of Spanish classical literature, Cervantes finds parallel in the opposition between brutal Visigoths and noble Basques and the harsh treatment which the Spanish handed out to the Moors. Don Quixote in the end sides with a Moorish lover (Abindarráez), against his Christian rival. Most remarkably, the book itself is revealed to be written by a Moor, Cide Hamete Benengeli and includes a long passage identifying all the Spanish words that come from Arabic language, such as almorzar, to have lunch.

After having brutally expelled the heretics, signs of regret began to appear. This ambivalence is particularly strong in the classic novel of Spanish literature, Don Quixote. The story of the knight-errant and his squire takes the form of a journey south, from Castile and towards Seville. In the course of his adventures, Quixote feels free to identify any untrustworthy character as an Andalusian moor. However, in attempting to revive the earlier romances of Spanish classical literature, Cervantes finds parallel in the opposition between brutal Visigoths and noble Basques and the harsh treatment which the Spanish handed out to the Moors. Don Quixote in the end sides with a Moorish lover (Abindarráez), against his Christian rival. Most remarkably, the book itself is revealed to be written by a Moor, Cide Hamete Benengeli and includes a long passage identifying all the Spanish words that come from Arabic language, such as almorzar, to have lunch.

At the end of Don Quixote, a lead box is found that contains laudatory poems. This alludes to the lead books that were supposedly discovered in Granada in early sixteenth century. Known as the plomos, they contained manuscripts in Arabic, supposedly signed by St. Cecilio, which implied that Granada was at the heart of the mystery of Immaculate Conception. They were in fact forgeries attempting to show that the Moriscos were actually early Christians, thus deserving respect.

The north-south fault line re-emerged in the twentieth century with the Spanish Civil War. The Republican forces were focused in the south-east of the country, supported particularly by Catalan radicals. Soon after the war began, the Republican poet Garcia Lorca was murdered by fascist forces. Lorca had championed the South as the spiritual home of ‘duende’, the dark passion that informs great art, embodied in the cante jondo (deep song) of Flamenco singing.

The north-south fault line re-emerged in the twentieth century with the Spanish Civil War. The Republican forces were focused in the south-east of the country, supported particularly by Catalan radicals. Soon after the war began, the Republican poet Garcia Lorca was murdered by fascist forces. Lorca had championed the South as the spiritual home of ‘duende’, the dark passion that informs great art, embodied in the cante jondo (deep song) of Flamenco singing.

The continuing feeling for the South as a region of the vanquished past is evoked in Victor Erice’s film, El Sur, which conflates the rift between families caused by the civil war and a story of love lost in the division between south and north. One of the films touching scenes is during the daughter’s first communion when she dances with her father, joining together the southern past with the northern present.

Given more recent tensions in the Middle East, this south of Spain has become particularly interesting as a region where the three religions of Islam, Judaism and Christianity were seen to co-exist relatively peacefully and productively. The Convencia was known particularly for its philosophy: scholars such as Averroes developed the Greek classical tradition of Aristotle into systems of thought that would lay the ground for Scholastics such as Thomas Aquinas.

What joined these philosophers was a sense of the limits of knowledge. Maimonides in the Guide for the Perplexed developed an apophatic theology which argued that divinity could never be understood within human terms, only negatively. In the early 12th century, Ibn Tufail wrote a philosophical novel, which was eventually translated into English as Improvement of Human Reason: Exhibited in the Life of Hai Ebn Yokdhan. This tale of a man who grows up isolated from all civilisation inspired the first novel in English, Robinson Crusoe. Tufail encouraged Averroes (Ibn Rushd) to write his commentaries on Aristotle, which developed the belief that ‘existence precedes essence’. Such views had a strong influence on the Enlightenment and secular views that emerged much later in eighteenth century Europe.

What joined these philosophers was a sense of the limits of knowledge. Maimonides in the Guide for the Perplexed developed an apophatic theology which argued that divinity could never be understood within human terms, only negatively. In the early 12th century, Ibn Tufail wrote a philosophical novel, which was eventually translated into English as Improvement of Human Reason: Exhibited in the Life of Hai Ebn Yokdhan. This tale of a man who grows up isolated from all civilisation inspired the first novel in English, Robinson Crusoe. Tufail encouraged Averroes (Ibn Rushd) to write his commentaries on Aristotle, which developed the belief that ‘existence precedes essence’. Such views had a strong influence on the Enlightenment and secular views that emerged much later in eighteenth century Europe.

It was through the Convivencia that the West ‘discovered’ Arabic numerals, paper, rice, sugar, cotton and the tradition of courtly love poems, including troubadours. From this perspective, the Reconquista seems like an act of grand theft, in which the benefits of civilisation were stolen and all traces of their previous ownership removed. But that would be to forget the curiosity about this abandoned past that continued to shadow the glories of the Spanish nation. Recent gestures like Erice’s El Sur attempt to rediscover how those pieces might fit together.

The possibility of reconciliation continues to haunt contemporary Spain. It’s part of a larger story about the two Europes – the modern North and backward South. The price of victory in the North came at the cost of the heartfelt traditions it seems to yearn for in its lost South. Whether or not reconciliation is possible, this dialogue continues to define the identity of Europe.

References

José Colmeiro ‘Exorcising exoticism: Carmen and the construction of oriental Spain’ Comparative Literature (2002) 54: 2, pp. 127-144

Judith Etzion ‘Spanish Music as Perceived in Western Music Historiography: A Case of the Black Legend?’ International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music (1998) 29: 2, pp. 93-120

Nicholás Wey Gómez The Tropics of Empire: Why Columbus Sailed South to the Indies Cambridge, Mass: MIT, 2008

Eric Clifford Graf Cervantes and Modernity: Four Essays on Don Quijote Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2007

A. Katie Harris From Muslim to Christian Granada: Inventing A City’s Past In Early Modern Spain Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007

Michael Richards A Time Of Silence: Civil War And The Culture Of Repression In Franco’s Spain, 1936-1945 : Cambridge University Press, 1998, pp. 67-69