Spernere mundum, spernere te ipsum, spernere te sperni.

Scorn the world, scorn yourself, scorn being scorned.

St Filippo Neri quoted by Goethe

The Faustian quest

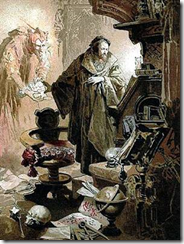

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is today the proud hero of enlightened Germany. Institutes in his name disseminate German culture around the world. And the core of this culture, Das Drama der Deutschen, is Goethe’s most key work, Faust (1808). Goethe’s drama turns on a deal between Mephistopheles and Faust: Mephistopheles will do the hero’s bidding on earth if he can show Faust a moment that we would like to last forever. The contract embeds a critical paradox: a quest in which the ultimate goes is to be free of the need to quest.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is today the proud hero of enlightened Germany. Institutes in his name disseminate German culture around the world. And the core of this culture, Das Drama der Deutschen, is Goethe’s most key work, Faust (1808). Goethe’s drama turns on a deal between Mephistopheles and Faust: Mephistopheles will do the hero’s bidding on earth if he can show Faust a moment that we would like to last forever. The contract embeds a critical paradox: a quest in which the ultimate goes is to be free of the need to quest.

In the case of Faust, the assumption is that the state of acceptance represents the ultimate goal of life—to be happy where one is. It opposes the restless questing for a distant goal against the simple acceptance of life as it is. This is an opposition between today and tomorrow, the relation between the ground under your feet and the horizon beyond, sequence of noon above and sunset disappearing, and, in the Germany story particularly, the relation of South to North.

This simple opposition between here and there provides a way of reading the idea of South in German culture. There are moments when tomorrow eclipses today and North triumphs over South. And there is an alternative line whereby the ground under one’s feet offers blessed relief from the ever receding horizon beyond, and South supersedes North. In the case of Goethe, we see a balance between both.

For Goethe personally, this opposition is played out during his journey through Italy. He contrasts the happy lives of Neapolitans against the deferment of pleasure in the North:

Nature compels the Northerner to make provisions and preparations, the housewife to pickle and cure, so as to supply the kitchen for the whole year, the husband to see to the stores of wood and grain, the fodder for the cattle, etc. Consequently the most beautiful days and hours are lost to enjoyment and devoted to work… These natural influences, which have stayed the same for millennia, surely have determined the character of northern nations, which are admirable in so many respects.[1]

Goethe’s Italian Journey is told as a struggle between his restless German self and the ‘school of light and merry living’ that beckoned him in Naples and Sicily. Goethe identified with the Northern mentality, while acknowledging the lack of Southern equanimity.

Other thinkers, however, turn this confirmation of North identity into a condemnation of the South. Others still reverse this hierarchy and see the Southern equanimity as superior to the distracted North. And then within Germany itself is its own internal division between North and South that is constitutive of its national identity.

The Classical Ideal

Goethe’s travel to Italy was inspired by Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s pioneering treatise on classicism, History of Ancient Art (1764). Winckelmann articulated a positive relation to South, at least to Germany’s immediate south in the sites of classical civilisation, Italy and Greece.

Goethe’s travel to Italy was inspired by Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s pioneering treatise on classicism, History of Ancient Art (1764). Winckelmann articulated a positive relation to South, at least to Germany’s immediate south in the sites of classical civilisation, Italy and Greece.

The cosmography for this classical world was derived by Winckelmann from the Aristotelian theory of climate. In Aristotle’s position, extremes of climate focus the individual on physical needs, while temperate environs such as in Italy or Greece enabled creativity to flourish: ‘A flower withers beneath an excessive heat, and, in a cellar into which the sun never penetrates, it remains without color.’[2] While this understanding may seem to position Germany unfavourably, at the cold extreme where little grows, Winckelmann’s project has been interpreted as aligning Germany culture with the classical ideal.

Enlightenment

With the enlightenment came a notion of modernity that distinguished forward looking nations from those oriented backwards. Immanuel Kant’s essay Answering the Question: What is Enlightenment? (1784) argues that ‘Enlightenment is mankind’s exit from self-incurred immaturity’. In this can be seen a foundation for the difference between an active North and a dependent South.

With the enlightenment came a notion of modernity that distinguished forward looking nations from those oriented backwards. Immanuel Kant’s essay Answering the Question: What is Enlightenment? (1784) argues that ‘Enlightenment is mankind’s exit from self-incurred immaturity’. In this can be seen a foundation for the difference between an active North and a dependent South.

Kant clearly believes that the world is not equal, but he refrains from geographic determinism. In his earlier text On the Different Races of Man (1775), Kant had argued for the superiority of the German peoples. Though Kant had a lifetime interest in geography, he did not subscribe to the climate as a cause for racial hierarchy. Such would contradict his overall philosophy of freedom. In his Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View (1798) he argues that ‘it does not depend on what Nature makes of man, but what man makes of himself.’ For Kant, the critical factor determining racial hierarchy was less defined, amounting to a kind of infection that afflicted the darker peoples.[3] Though maybe not part of Kant’s world view at the time, his categorial imperative (the moral principle of reciprocity, that one acts as one would wish others would act) can be seen as a driving force in the development of new southern perspectives, which seek more reciprocal intellectual exchange between the West and its other.

What the dialectic leaves behind

In the case of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, however, there were clear reasons in nature why the North was superior to the South.

In the case of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, however, there were clear reasons in nature why the North was superior to the South.

In his lectures on the philosophy of history (1837), Hegel placed Germany in a privileged position to inherent the mantle of civilisation from the classical world. He developed the Aristotelian position beyond a simple symmetrical relation between North and South, cold and hot. For Hegel, history demonstrates that the North is privileged:

The true theatre of history is therefore the temperate zone; or, rather, its northern half, because the earth there presents itself in a continental form, and has a broad breast, as the Greeks say. In the south, on the contrary, it divides itself, and runs out into many points.[4]

Hegel distinguishes a developed North from an undeveloped South. To argue this point, he cites the case of the nature in New Holland, where streams have not developed channels as rivers but ‘lose themselves in marshes’.[5] The world contains an obvious vertical hierarchy.

Laterally, Hegel articulates the Occidentalist position that progress follows the sun, therefore ‘The History of the World travels from East to West, for Europe is absolutely the end of History, Asia the beginning.’[6] But while the sun may once have shone in countries like India and China, it has never graced the dark expanse of Africa—‘the land of childhood, which, lying beyond the day of self-conscious history, is enveloped in the dark mantle of Night.’[7] So while the lateral journey of the sun places east in the beginning (dawn) and west at the end (sunset), the South is a permanent night. In this vision of a dark South, Hegel extends the solar trope beyond analogy into pure metaphor.

Nordic ideals

By the nineteenth century, this conceptual hierarchy of North and South began to take political form as a belief emerged in the racial supremacy of Nordic peoples. In 1851, Schopenhauer argued for the superiority of the white races in direct contradiction with Aristotle. It was the very physical hardships experienced by white peoples in their migration north that equipped them with powers of invention.

By the nineteenth century, this conceptual hierarchy of North and South began to take political form as a belief emerged in the racial supremacy of Nordic peoples. In 1851, Schopenhauer argued for the superiority of the white races in direct contradiction with Aristotle. It was the very physical hardships experienced by white peoples in their migration north that equipped them with powers of invention.

This different became the subject of scientific study. In 1888, the Russian émigré known as Madam Blavatsky published The Secret Doctrine, the Synthesis of Science, Religion and Philosophy which focused this argument particularly on the Aryan races. In 1930, the leading intellectual forces of the Nazi movement, Alfred Rosenberg, published The Myth of the Twentieth Century which located the origins of the Aryans on a lost landmass off the coast of north-west Europe, from where they spanned eastwards to found civilisations as far as Iran and India.

Such views serviced Germany’s colonial ambitions. In the early 20th century, these views were used to justify the policies of the Deutsch Ostafrikanische Gesellschaft in Africa, for whom ‘The purpose of colonization is, unscrupulously and with deliberation, to enrich our own people at the expense of other weaker peoples.’[8] In 1903, German colonists invaded Namibia displacing the Herero people who subsequently rebelled. In response, the Germans drove the Herero into the deserts and poisoned wells, herding the survivors into concentration camps to work as slave labourers. This is regarded as the world’s first genocide, and a rehearsal for the later extermination of Jews. In response to international protest at the time, the Germans claimed that the Herero were sub-humans.

Such views serviced Germany’s colonial ambitions. In the early 20th century, these views were used to justify the policies of the Deutsch Ostafrikanische Gesellschaft in Africa, for whom ‘The purpose of colonization is, unscrupulously and with deliberation, to enrich our own people at the expense of other weaker peoples.’[8] In 1903, German colonists invaded Namibia displacing the Herero people who subsequently rebelled. In response, the Germans drove the Herero into the deserts and poisoned wells, herding the survivors into concentration camps to work as slave labourers. This is regarded as the world’s first genocide, and a rehearsal for the later extermination of Jews. In response to international protest at the time, the Germans claimed that the Herero were sub-humans.

Nordicism was associated with particular physical features, such as dolichocephalic heads (long-skulled), blond hair, blue eyes and tall stature. In 1933 Nazi theorist Hermann Gauch argued that birds can be taught to talk better than other animals because ‘their mouths are Nordic in structure.’ Such racial superiority became the justification for conquest. For Adolf Hitler, the German quest was to plant the ‘seed of Nordic blood’ and so regenerate the world.

Nordicism was associated with particular physical features, such as dolichocephalic heads (long-skulled), blond hair, blue eyes and tall stature. In 1933 Nazi theorist Hermann Gauch argued that birds can be taught to talk better than other animals because ‘their mouths are Nordic in structure.’ Such racial superiority became the justification for conquest. For Adolf Hitler, the German quest was to plant the ‘seed of Nordic blood’ and so regenerate the world.

This quest to conquer the South reached its apotheosis with the Third Reich—so ends the story of Northern superiority. But this is not the only German story. Amongst a parallel line of thinkers we can see alternative attitudes, sometimes even reversing the relation between Northern struggle and Southern acceptance.

The ‘great noon-calm’

According to the dominant narrative, the restless North overcomes a lazy South. But there were many for whom this hierarchy was reversed—the dislocated North seeks a centred South. Oswald Spengler published Decline of the West in 1918, arguing for an organic notion of culture that grows and dies. He described Gothic architecture as the expression of a Faustian North, with its focus on the ‘I’ and flying buttresses.

He contrasted this against the Apollonian South, realised in Renaissance, whose contribution is that ‘in lieu of the Northern Sturm und Drang it breathed the clear equable calm of the sunny, carefree and unquestioning South.’[9] The Renaissance gave expression to the ‘fullness of light, the clarity of atmosphere, the great noon-calm, of the South’. While still elevating the Northern Gothic as a source of innovation, Spengler shared Goethe’s understanding of the South as an alternative way of being.

The reversal of value was given most powerful expression by Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche criticised the Aristotelian hierarchy of temperate zones and praised ‘tropical man’. In Beyond Good and Evil (1886), Nietzsche continued his attack on Christianity, particularly northern Protestantism.

The reversal of value was given most powerful expression by Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche criticised the Aristotelian hierarchy of temperate zones and praised ‘tropical man’. In Beyond Good and Evil (1886), Nietzsche continued his attack on Christianity, particularly northern Protestantism.

He contrasted the heavy German music of Wagner with the ‘childish delight’ of Mozart. The Northern German is ‘manifold, formless, and inexhaustible’, associated with clouds, twilight and dampness—all that is still in the process of development. In Wagner, one finds ‘no beauty, nothing of the south, nothing of the fine southern brightness of heaven, nothing of grace, no dance, scarcely any will for logic’. The Germans ‘belong to the day before yesterday and the day after tomorrow—but they still have no today.’

One of Nietzsche’s key ideas is the Eternal Return of the Same, in which we are bound to experience our immediate present forever, invalidating the ceaseless questing beyond. Like Goethe’s Faust, Nietzsche focused on the elusive quest to be without quest.

Caught between North and South

In the arts, the division between North and South is often more balanced. Thomas Mann’s novella Tonio Kröger (1898) seeks to understand how this opposition can be contained within a single person. The hero is born of a Puritanical German father and impulsive Italian mother. He escapes the bourgeois comforts of the north for the ‘cities of the south’, ‘for he felt that his art would ripen more lushly in the southern sun’.[10] Yet there is a time we he also seeks the heartfelt melancholy of the North, fleeing to Denmark, saying ‘I can’t stand all that dreadful southern vivacity, all those people with their black animal eyes. They’ve no conscience in their eyes, those Latin races.’[11] In the case of Mann, this incommensurability of North and South is a source of tragedy.

In the arts, the division between North and South is often more balanced. Thomas Mann’s novella Tonio Kröger (1898) seeks to understand how this opposition can be contained within a single person. The hero is born of a Puritanical German father and impulsive Italian mother. He escapes the bourgeois comforts of the north for the ‘cities of the south’, ‘for he felt that his art would ripen more lushly in the southern sun’.[10] Yet there is a time we he also seeks the heartfelt melancholy of the North, fleeing to Denmark, saying ‘I can’t stand all that dreadful southern vivacity, all those people with their black animal eyes. They’ve no conscience in their eyes, those Latin races.’[11] In the case of Mann, this incommensurability of North and South is a source of tragedy.

We can see modern versions of this with films such as Doris Dörrie’s Bin ich schon? (Am I Beautiful?) In this road movie, a German family undertakes the epic journey across to Spain for a holiday. In the process, the film continually contrasts the obsessive German mentality with Spanish spontaneity.[12] For Dörrie, the passion of the South undercuts Northern pretensions.

While the South may be variously charged positively or negatively, it is inevitably cast as other to German culture. But what is authentic German culture? The popular image consists of men in lederhosen slapping their thighs, drinking steins of beer and ogling at the maidens in dirndls. The ‘Oktoberfest’ Germany is only a recent appendage—Bavaria is only a late addition to the German kingdom. Indeed, the internal polarity between Bavaria and Prussia may almost be as stark as the external difference between Germany and Italy.

The South within

As the ‘Texas of Germany’, Bavaria’s folk culture is at odds with the restless Prussian north. Its Catholic culture reflected a traditional allegiance to ritual contrasting with the austerity of the Protestant north.

As the ‘Texas of Germany’, Bavaria’s folk culture is at odds with the restless Prussian north. Its Catholic culture reflected a traditional allegiance to ritual contrasting with the austerity of the Protestant north.

From the north, Bavaria is seen as a quaint and ridiculous region. When Bismarck was manoeuvring to incorporate Bavaria into the German state in 1866, he described the typical Bavarian as ‘half-way between an Austrian and a human being’. Eventually, when the treaty between north and south was being framed, the Jewish founder of the National Liberal Party, Eduard Lasker, advised, ‘The girl is very ugly indeed, but nevertheless she must be married.’ Bavaria was a necessary evil, wrested from Austria to bolster the Prussian state.

The treaty was negotiated with ‘mad’ King Ludwig II, who is most famously remembered today for squandering his kingdom’s fortunes on personal follies. But as with most southern stereotypes, there’s another side the story. Luigi Visconti’s film version of Ludwig’s biography constructs a scenario parallel to his depiction of Sicily in The Leopard: a proud aristocrat attempts to sustain the magnificence of his position against the odds of an ambitious new bourgeoisie. Bavaria is proud, sensitive, cultivated, while Prussia is brazen, boorish and philistine.

There is a strain of German culture which expresses Drang nach dem Süden, a yearning for the South. This is a South of acanthus leaf, orange grove and marble colonnade. It is a world of fantasy and wonder, far from the austere Prussian north.[13]

For the Altbayen, Prussia was an upstart nation. The word ‘Preuss’ was used in Bavaria to describe any unwelcome foreigner. Bavaria’s great cultivation was reflected in the capital, Munich, known as the ‘Athens of Isar’. Its destiny as a cultural capital culminated in the majestic Ring Cycle, staged for Wagner by King Ludwig in the town of Bayreuth. Later the English writer Walter Pater evoked the image of King Ludwig as a ‘northern Apollo’…’god of light, coming to Germany from some more favoured world beyond it, over leagues of rainy hills and mountain, making soft day there.’ To a degree this creative leadership continues today in jewellery, where exchange with the Munich Academy in Australia and New Zealand has inspired their own cultures of adornment.

Conclusion

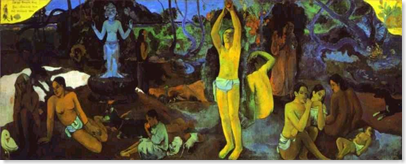

While this is a core story of the German idea of south, it cuts short at the significant German interest in the Southern world, particularly the Pacific. This includes the German presence in New Guinea, Solomons, Samoa, the settlements in South America, as well as the extensive network of Lutheran missions in Australia. Germany is likely to be a regular presence as the idea of south continues its journey.

In the case of Germany, we find a fraught story that seems to realise the most extreme version of Southern inferiority. Yet because of this, there are lines of thought that develop quite a strong idea of south—as an eternal midday, clear, still and in the moment.

[1] J.W. Goethe

Italian Journey (trans. Robert R. Heitner) New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1994 (orig. 1786), p. 265

[2] Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s History of Ancient Art (translated by Giles Henry Lodge) J. R. Osgood, 1849, p.36

[3] See Jonathan Goldberg Tempest In The Caribbean Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004

[4] G.W.F. Hegel The Philosophy Of History (trans. J. Sibree) New York: Dover, 1956 (orig. 1831), p. 80

[5] The Australian writer Paul Carter has described this anxious policing of boundaries between water and land as ‘dry thinking’.

[6] G.W.F. Hegel The Philosophy Of History (trans. J. Sibree) New York: Dover, 1956 (orig. 1831), p. 103

[7] G.W.F. Hegel The Philosophy Of History (trans. J. Sibree) New York: Dover, 1956 (orig. 1831), p. 104

[8] Marc Ferro Colonization: A Global History (trans. K.D.Prithpaul) London: Routledge, 1997 (orig. 1994), pp. 83-84

[9] Oswald Spengler The Decline of the West (trans. Charles Francis Atkinson) New York: Vintage, 2006 (orig. 1918), p. 123

[10] Thomas Mann ‘Tonio Kröger’, in (ed. ) Death in Venice and Other Stories (trans. David Luke) London: Vintage, 1998 (orig. 1903

[11] Thomas Mann ‘Tonio Kröger’, in (ed. ) Death in Venice and Other Stories (trans. David Luke) London: Vintage, 1998 (orig. 1903), p. 167

[12] Peter M. McIsaac ‘North-South, East-West: Mapping German Identities in Cinematic and Literary Versions of Doris Dorrie’s “Bin ich schön?”’ The German Quarterly (2004) 77: 3, pp. 340-362

[13] Christopher McIntosh The Swan King, Ludwig II of Bavaria London: A. Lane, 1982, p. 11

Now the South has become a significant luxury brand, associated with the region of Provencal in cuisine and home goods. Olivier Baussan founded the company l’Occitane, ‘L’OCCITANE has drawn inspiration from Mediterranean art de vivre and traditional Provencal techniques to create natural beauty products devoted to well-being and the pleasure of delighting and caring for oneself.’ This company has now extended its southern taste to other countries. The brand L’Occitane do Brasil expresses the authenticity of a first natural sun care line made exclusively in Brazil.

Now the South has become a significant luxury brand, associated with the region of Provencal in cuisine and home goods. Olivier Baussan founded the company l’Occitane, ‘L’OCCITANE has drawn inspiration from Mediterranean art de vivre and traditional Provencal techniques to create natural beauty products devoted to well-being and the pleasure of delighting and caring for oneself.’ This company has now extended its southern taste to other countries. The brand L’Occitane do Brasil expresses the authenticity of a first natural sun care line made exclusively in Brazil.