The Mauritian writer Lindsay Collen has responded to the story of Mauritius as ‘an island of mistakes’ with a critical analysis of colonial myths. In particular, she critiques the way Mauritius is reduced, in terms of space and language. It’s a long piece, but worth presenting in full for the issues it raises more generally about the ‘small’ nations of the South.

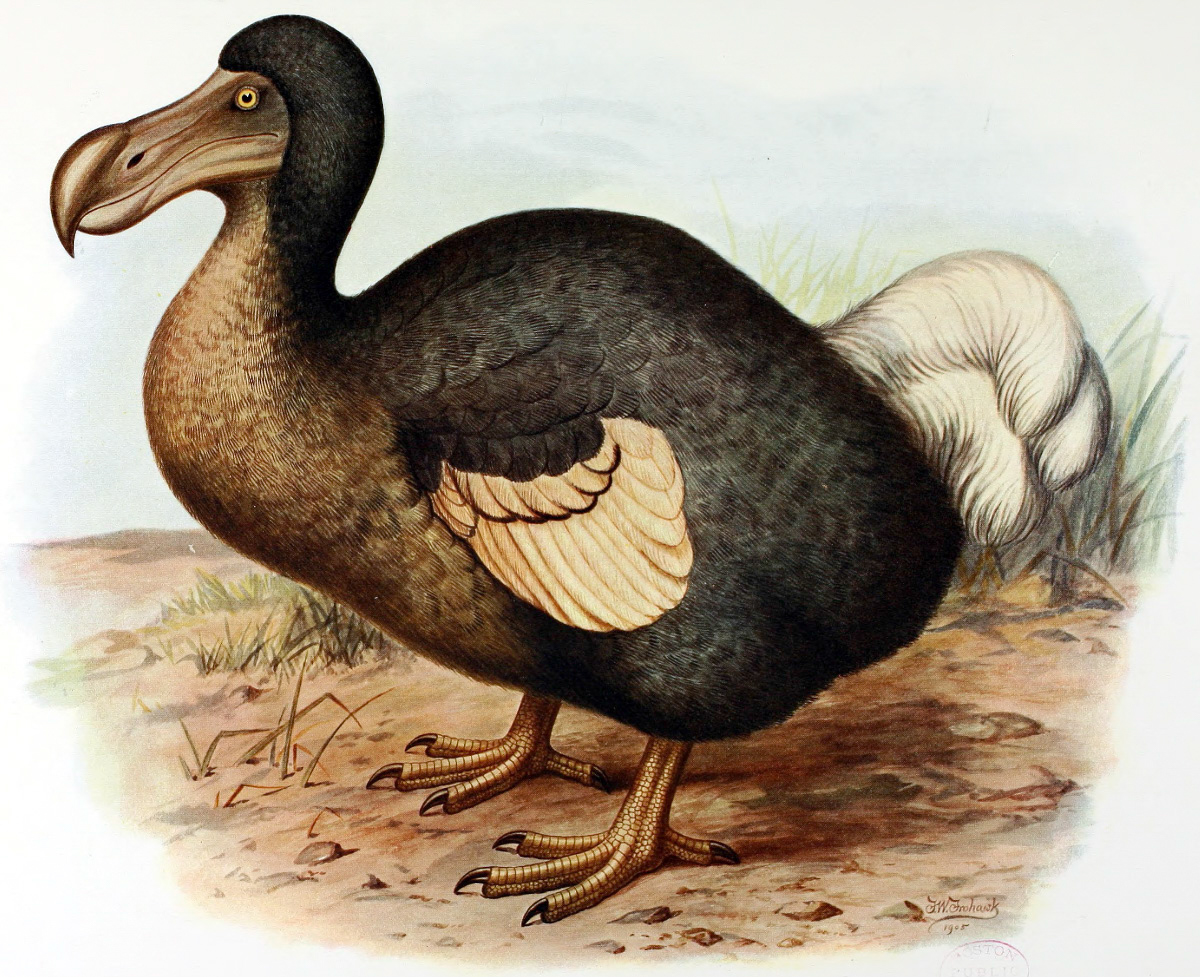

Mauritius keeps on being a place for mistakes. After the most valuable stamp because of a typo, and after being a home to the mistaken creature the dodo, people, even the most sophisticated, even the most erudite, continue to make mistakes when they talk about Mauritius. Often real howlers. And the mistakes are often interesting, in that they are a bit like a social version of Freudian slips of the tongue. They unveil something hidden in the collective unconscious. Something awful. If we take a look at a few of these ‘mistakes’, we’ll find that they mask hidden political secrets and buried social pathologies. And we’ll also find that these secrets and pathologies are not hidden innocently. The hiding plays right into the hands of oppressors. The mistake then becomes a form of ‘identifying oneself with the oppressor’ or ingratiating oneself with him (usually a ‘him’). Let me explain by way of two or three examples.

‘Mauritius is a Small Island … ?’

People, even Mauritians, invariably start conversations about Mauritius by saying ‘Mauritius is a small island …’

Mistake.

A very widespread mistake, too. I did a little exercise with 112 A-level students at the country’s supposedly second-most-sought-after girls’ secondary school a couple of years ago when I was a guest speaker. I asked them to write a paragraph about their country for a visiting Martian or Venusian, differentiating it from other States. Over 90% began with the dratted phrase. ‘Mauritius is a small island …’

Mauritius, the country, is, in fact, made up of many islands: the Islands of Mauritius, Rodrigues, Agalega, St. Brandon, for a start, and if we pretend Mauritius is one island only, we are denying the existence of the human beings on the other Islands. Strange, cruel chauvinism. But there’s more to come. Mauritius consists of yet other Islands still. Tromelin, for example. It is occupied illegally by France. The Mitterrand political programme of 1982 before his first election promised the return of Tromelin to Mauritius. The promise stayed a mere promise. The Island itself is now hidden in our talk of ‘Mauritius is a small island …’

And stranger still. One hundred and twenty-four Chagos Islands were illegally excised from the Mauritian State by Britain in the run-up to Independence, and are occupied by Britain until today. This is against the United Nations Charter. But there you go. ‘Mauritius is a small island …’ . Stranger still, the main Chagos Islands called Diego Garcia is now the geographical location for a huge United States military base, the very base from which B-52’s take off to bomb, say, a marriage party on a road between two villages in Afghanistan, or a market-place in Iraq. But Diego Garcia is nowhere. It is not part of Mauritius. ‘Mauritius is a small island …’

So, when you say ‘Mauritius is a small island …’ you are covering up the illegal occupation of much of Mauritius’ territory by colonial powers, as well as masking who it is exactly who is, democratically speaking, responsible for allowing Diego Garcia to be a major trampoline for war and mass murder. And who is responsible for putting an end to the illegal renderings that Gordon Brown has confessed go on there? The British people? Why, they hardly knew the stolen islands existed until a few years ago when the displaced people began winning High Court cases against the British State in London. The American people? They may know about it if they have brothers or sisters, sons or daughters who are in the armed forces and have been stationed at Diego Garcia, or ‘DG’ as they call it, intuitively hiding its real name. Otherwise, Americans in general do not know that they are, democratically speaking, at least partly responsible for what goes on there. Mauritians know, but we, as you know by now, are a small island … There can’t very well be another island inside the first one, let alone an archipelago. And, so small we are that we don’t count. See the damage done to our minds! In this little phrase ‘Mauritius is a small island’.

If Mauritius is ‘a small island’, then who bears responsibility for having forced the Mauritians living on Diego Garcia off their home Islands, since by pure grammar, Diego Garcia cannot be in Mauritius? If Mauritius is ‘a small island’, clearly it’s not important that Mauritians mobilize to force our Government to put in a case for an Advisory Opinion before the United Nations International Court of Justice at The Hague, in the process of re-uniting Mauritius. How could you re-unite it? It is and always has been ‘a small Island’. So, if Mauritius is one small Island, it wouldn’t be our responsibility, democratically speaking, to get the base closed down forever.

So, the mistake is not an innocent one. It perpetuates the mysterious silence of the world on one of the major crimes of Britain and the United States. It covers them up. Behind words that look, to all intents and purposes, like ‘a mistake’.

Smallness also means insignificance. A country is its land area and sea area. Mauritius is a huge country if judged by its territorial waters. Nearly as big as India, according to the Indian army! But so long as we believe we are so very ‘small’, then how can we kick the huge British and huger still Americans out of Diego Garcia?

‘Mauritius is Francophone … ?’

The second sentence I’ll take as an example of a common ‘mistake’ is when people say, and this is even in the first page of the South site I’m writing this for: ‘Mauritius is a Francophone Island’. France says this in its Government propaganda, and France has a Ministry of ‘la Francophonie’, so they should know what they are talking about. However, the truth is that 3.2% of the Mauritian people claim (French is very high status so the figure is, if anything, an exaggeration) that they usually speak French at home. This is according to the last door-to-door census in 2000. If you say that ‘Mauritius is a Francophone country’, this false statement then must somehow mean that the Mauritian languages, Kreol and Bhojpuri, spoken by 92% of the people, are perhaps not really languages at all. And if a human society does not have language, or its languages don’t count, then there is an assumption that the people in that society are somehow sub-human.

‘Mauritian Kreol is derived from French …?’

Following on from this, when people finally give up on the ‘Mauritius is a Francophone Island …’ line, they then say Mauritians speak a Creole ‘derived from’ French. Fortunately most people have stopped saying Mauritian Kreol is a ‘patois’, ‘broken French’, ‘a composite of different languages’, ‘gutter French’, a ‘baragouin’ or ‘charabia’.

But the ‘derived from’ expression is still used by people who should know better. It is used even by academics – in all departments at Universities except for the theoretical linguistics departments. Even a socio-linguistics department may have academics in it that say Mauritian Kreol is ‘derived from’ French. Meanwhile, for over 50 years now, the 80 of so Creole languages that exist in the world have been known to have been born from a break, not from a gradual evolution like other languages. (Most Creole languages, by the way, exist in relation to English, which is also a little known fact, and then also to French, Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese, and Arabic). Creole languages are the 80 languages out of the world’s 9,000 that are most clearly not ‘derived from’ another or other languages. Creole languages, including Mauritian Kreol, are born from a historical fracture. The ‘fracture’ which is covered up, hidden from view, by the euphemism ‘Mauritian Kreol is derived from French …’ is slavery. The process by which a new language is born quite suddenly, as Creole languages are, is that, as one generation of children grows up amongst adults speaking often dozens of different mother-tongues – having been thrown together by a holocaust like slavery – they use the innate human ‘language capacity’ that we all have and, within one generation, generate a brand-new, absolutely perfect language from the detritus around them, after this social holocaust called slavery. Such is the power of our shared human language capacity. When we say ‘language’ we are referring essentially to the grammatical structures of language (predication, syntax, etc).

But, since most people confuse language and think of it as lexical items, like beads that get strung together as if on a necklace, which it isn’t, let us look at the lexical items, anyway. Even the vocabulary is not ‘derived’ in any direct way from the colonial language, which the particular Creole language exists in relation to. ‘Get’ in Mauritian Kreol means to ‘look’, and people are very quick to take it as being ‘derived from’ the French ‘guetter’ which is ‘to lie in wait for’ or the marine expression ‘to be on the watch’. In French ‘regarde’ means to ‘look’, whereas in Kreol ‘regard’ is used uniquely in the negative meaning mind your own business. It’s hard to call this ‘derived from’, but it could be ‘in relation to’. In any case, to assume that ‘get’ comes from ‘guetter’ when one does not know the other 20 or more languages that were spoken by adults at the time of the genesis of Mauritian Kreol is clearly nothing but colonial presumption. Even educated people assume that ‘kurpa’ (‘snail’ in Kreol, which in French is ‘escargot’) going now into mythical attributes of snails must then come from the French ‘courts pas’ (short paces) or ‘court pas’ (doesn’t run), while they are unaware that there is a kind of snail in Mozambique called ‘kurupa’. The fruit in Kreol called ‘mason’ is assumed to be linked to the French meaning ‘mason’, when in Malawi people call the same fruit ‘masao’ (sounding just like nasalized ‘mason’ in Kreol).

The word ‘bann’ before a noun in Mauritian Kreol, has a function similar to the plural marker – a bit like an ‘s’ added on to a word is for English. So, all the colonial minds chant in unison: ‘This is derived from the French ‘une bande de’ meaning ‘a band of, or a troop’’. Maybe there is some vague and indirect connection, who knows? What we can say is that in good Mauritian Kreol, the plural marker is often assumed from the context and not expressed at all. Now that’s a fracture. In French you absolutely have to specify. That’s the most important point about the word ‘bann’, it exists in its suppression most of the time. Secondly, there is a plural marker in Nguni African languages that sounds just like ‘bann’ – but of course the universities in France are not full of people who know these languages. Many people may not know that ‘a person’, for example, in the Xhosa language is ‘umntu’ (pronounced nearer ‘mtu’), while the plural ‘people’ is ‘abantu’ pronounced quite near ‘bantu’ (hence in apartheid the word ‘bantustan’). Umntwana (pronounced near to ’mtwana) in the plural is ‘abantwana’ (pronounced near to ’bantwana). So, there are at least two ways to explain the choice of that sound as a plural marker, one rather more convincing than the other.

What is important about this particular mistake that Kreol is ‘derived from’ French is that as long as the Kreol language is considered somehow adulterated French, or ‘derived from’ French, it is easier to oppress it. In Mauritius the mother tongues spoken by 92% of the people are banned in written form in almost all schools until today. Recently Government subsidized pre-vocational schools have been permitted to use written Kreol, which is excellent, but note that it is so far only used … for the children who have ‘failed’. Thus re-enforcing the prejudice, in a way.

So, the mistakes continue. Until we stop them.

Just as we see that Mauritius was known, as well as for the erroneous stamp and the extinct dodo, for its sugar monoculture. Now that was a mistake for the people. And we feel it right now, as Mauritius plunges into an organic crisis, as sugar fails under new World Trade Organization rules. See LALIT’s website for details on this www.lalitmauritius.org

And today Mauritius’ economy is increasingly reliant on tourism. Another mistake.

Until we change it.

Meanwhile, the tourism ‘branding’ of Mauritius (like animals were branded long ago, and slaves, too) can teach us a thing or two about the power of the advertising industry to control our minds. Mauritius used — until about 1980 — to be seen from outside of the country as a generally filthy little overpopulated hell-hole of ‘an island’, Francophone, of course. It was considered smelly, too. All this was completely believed. At a time when Mauritius’ natural beauty was more stunning than now, of course. If you want to be reminded of the general impression people had of the place, you can read an eternalized version of it in the VS Naipaul short story, ‘The Overcrowded Baracoon’. But once the advertising boys (I think of them as men, which is unfair, but it is such a patriarchal, controlling profession) got their ‘magic system’ going to sell hotels, they have transformed the entire country into a paradise. A honeymoon paradise. A total paradise. Where the grass is rich lush green, but it never rains. Where there are no people, only stage props for the fantasies of tourists. Where everyone is happily living in multi-cultural harmony. Where there is no violence. Where there are no foul smells either.

And this is just as false, of course, as the ‘hell-hole’ view. One mistake has been traded for the 180 degrees opposite mistake.

Until we can share ideas and change it.

So, do read up about Mauritius beyond the tourist lies. The best history book to start with might be Daniel North-Coombes Studies in the Political Economy of Mauritius (Mahatma Gandhi Institute 2000) which is devoid of the prevailing prejudices. And there are lovely novels in French, Hindi and English as well as in Kreol.

Lindsey Collen

But this mixing of genres makes it difficult for Ahamah’s dance to find a place in Mauritius. There is official support for Indian and French culture in particular, but not so much for their combinations. Like many Mauritians who fall between the gaps, Ahamah has been active in creating spaces for new forms to emerge. He established his own dance company that recently performed "Feu De Paille”.

But this mixing of genres makes it difficult for Ahamah’s dance to find a place in Mauritius. There is official support for Indian and French culture in particular, but not so much for their combinations. Like many Mauritians who fall between the gaps, Ahamah has been active in creating spaces for new forms to emerge. He established his own dance company that recently performed "Feu De Paille”.

Behind these two clichés of Mauritian errantry lies a complex country. This Francophone island is populated largely by those of Indian descent. Though French speaking, for the past two centuries Mauritius has been a proud member of the British Commonwealth. There is a significant population of Creoles, descended from African slaves. Marginalised from official life, Creole culture developed a rich oral and musical tradition. The Sega is a national dance of Mauritius, which combines European polka with African rhythm. In the 1980s, this evolved into Seggae, by a Mauritian Bob Marley called Kaya, who was allegedly murdered while in police custody.

Behind these two clichés of Mauritian errantry lies a complex country. This Francophone island is populated largely by those of Indian descent. Though French speaking, for the past two centuries Mauritius has been a proud member of the British Commonwealth. There is a significant population of Creoles, descended from African slaves. Marginalised from official life, Creole culture developed a rich oral and musical tradition. The Sega is a national dance of Mauritius, which combines European polka with African rhythm. In the 1980s, this evolved into Seggae, by a Mauritian Bob Marley called Kaya, who was allegedly murdered while in police custody.