The idea continues its southward journey. We move from an island in the middle of the Indian Ocean to a tropical land which, though part of the Northern Hemisphere, crowns the continent of South America. Not just geographically in the northern half, Colombia is also widely seen as ally to its northern patron, the USA, resisting the ‘pink tide’ that has pushed its southern neighbours to the left. How does Colombia inform our understanding of South?

It should be noted that Colombia is a complex story and this is very much an external viewpoint, related to the ongoing search for south-ness. To help explore a little more deeply, a number of people familiar with the country have been asked to comment on what might be missing in the world if Colombia did not exist. They help us reflect on a country that evokes the violence of gratuity.

It begins with El Dorado…

On the shores of Guatavitá, a volcanic lake near present-day Bogatá, the new Zipa is prepared for the ceremony marking his ascension to the throne. He is stripped naked and covered with a sticky layer of balsam gum, on which gold dust is applied. Transformed into a golden figure, he steps on to a raft with other gold objects, including intricate votive figurines, tunjos. Once out in the centre of the lake, priests throw all the golden objects into the water, restoring the divine order of things. Finally, the Zipa plunges into the lake and swims to shore a new chief.

On the shores of Guatavitá, a volcanic lake near present-day Bogatá, the new Zipa is prepared for the ceremony marking his ascension to the throne. He is stripped naked and covered with a sticky layer of balsam gum, on which gold dust is applied. Transformed into a golden figure, he steps on to a raft with other gold objects, including intricate votive figurines, tunjos. Once out in the centre of the lake, priests throw all the golden objects into the water, restoring the divine order of things. Finally, the Zipa plunges into the lake and swims to shore a new chief.

This legend of the ‘gifted one’, El Dorado, soon spread throughout the newly colonised world. When riches ran out in Mexico, Europe turned its attention to the tropics, seeking the valley of wild cinnamon containing untold gold reserves. The brutal colonisation of the northern stretch of South America can be traced directly to the expeditions in search of El Dorado.

The fantasy of El Dorado was based on the hypothesis that there existed a culture in which gold was of no value. Gold in Central America was used only for adornment, rarely currency. The Aztec word for gold was teocuitlatl, or ‘excrement of the gods’. The value of gold was only as it was crafted into precious objects. A Panamanian chief could not understand why the Spanish would melt objects down into featureless ingots.[1] In Candide, Voltaire writes about Cacambo and Candide visiting El Dorado, which is an idyllic isolated valley run on strict communitarian principles. The King treats them with great kindness, but is amused with their love of gold, which he dismisses as ‘yellow mud’. Like the number ‘zero’, El Dorado served as a null state that underpinned the emerging mathematics of global trade.

The dream of untold wealth was not an auspicious beginning.

Fault lines

Colombia emerged as a nation from the Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1810, lead by the forces of Simón Bolívar. The Bolivarian dream of a United States of South America came to a cruel end as the Colombian federation was broken up by reactionary forces in Venezuela and Ecuador. The conflict became a ‘war to the death’ (guerra a muerte) where no prisoners were taken. As Eduardo Galeano comments on Bolivar’s demise: ‘Was this, was this history? All grandeur ends up dwarfed. On the neck of every promise crawls betrayal. Great men become voracious landlords. The sons of America destroy each other. ‘[2]

Colombia emerged as a nation from the Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1810, lead by the forces of Simón Bolívar. The Bolivarian dream of a United States of South America came to a cruel end as the Colombian federation was broken up by reactionary forces in Venezuela and Ecuador. The conflict became a ‘war to the death’ (guerra a muerte) where no prisoners were taken. As Eduardo Galeano comments on Bolivar’s demise: ‘Was this, was this history? All grandeur ends up dwarfed. On the neck of every promise crawls betrayal. Great men become voracious landlords. The sons of America destroy each other. ‘[2]

The fault-line of violence continues into the modern era, with today’s three-way conflict between the government and left and right-wing guerrillas. The writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez describes the atrocities that have become part of everyday life in Colombia as a ‘Biblical Holocaust’. His News of a Kidnapping documents the national obsession with guerrillas, including children’s birthday parties broadcast on national television in the hope that their kidnapped parents may still be alive and encouraged by the happy scenes.

In this context, the fiction of Gabriel Garcia Marquez appears as a kind of imaginary haven from the violence outside. For Marquez, the world of fantastic places like Macondo in 100 Years of Solitude reflects the true nature of Colombian life. As he said in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech: ‘Poets and beggars, musicians and prophets, warriors and scoundrels, all creatures of that unbridled reality, we have had to ask but little of imagination, for our crucial problem has been a lack of conventional means to render our lives believable.’

The happy sublime

Yet rather than succumbing to gloom, Colombia seems to counter violence with festivity. According to the Happy Planet Index, Colombians are among the happiest people on earth, second only to Vanuatu. This certainly reflects on the carnival of cambia, salsa, food and sex that is celebrated at the Colombian way of life. Colombian artists respond to this contradiction between reality and mood in different ways.

The artist Maria Fernando Cardoso has produced a number of exhibitions in Australia, including Zoomorphia in which animals perform baroque feats such as flea circuses. When considering what is unique to Colombia, Cardoso nominates its regional specialisations, ‘…being a particular Lechona (roasted pork) a Ternera a la Llanera, an Ajiaco, a Casuela de Mariscos, Cuajada con Queso, Melcoha, Alfandoque, Chicha, Arepa de Choclo, Pandeyuca, Almohabana, Chocolate Caliente, etc. Colombia one of the most diverse countries I know, there are differences from town to town’ For Cardoso, Colombia is a nation of artists, including ‘street people, street culture, los recicladores, los vendedores ambulantes.’

|

|

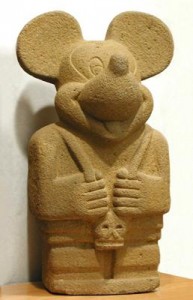

The artist Nadín Ospina created a series of work that reflected on the penetration of capitalism into Colombian identity. He commissioned objects from artisans who forged pre-Colombian artefacts and so produced objects incorporating Western icons like Mickey Mouse and Bart Simpson. His most recent work Colombialan uses the style of a children’s Lego game to reflect on the unreality of guerrilla violence. Ospina is critical of the escapist culture of Colombia; he says, ‘A society used to its pain and its violence is a society incapable of finding a solution to its conflicts.’

Oscar Muños gives expression to the fraught progress of Colombian politics with a series of portraits that require active participation in order to remain visible. Breath requires the viewer to breathe on steel plates to see the face, while in Project for a Memorial the face evaporates as it is drawn. The work evokes an anxiety about the lack of political progress.

What if Colombia did not exist?

Gabriela Salgado (curator, Tate Modern) sees Colombia as the projection of global anxieties:

Colombia is larger than the imagination and more positive than its media profile, which always associates the country with war, violence and drug production. If it did not exist, the ignorance- propagation machine of the global media would invent another Colombia to fulfil the need for gore and negativity with which invests selected parts of the world. On the other hand, if it did not exist, I would have not seen one of the most beautiful natural sanctuaries in the planet, and we would be missing a great deal of high quality contemporary art, literature, film, music, and intellectual production.

Jeff Browit (Coordinator of Contemporary Latin America at University of Technology Sydney) located Colombia firmly in the south:

Colombia is geographically ‘north’ of the equator, but philosophically ‘south’ in that it has a legacy of Iberian invasion and the imposition of an Iberian version of Westernisation and Christianity. It has subsequently laboured under neocolonial pressures from the United States and found itself trapped at times in the Cold War logics of the US-Soviet struggle for hearts and minds. In that sense it shares a common experience with many countries deemed part of the ‘south’. Aside from these geopolitical implications, it has an extraordinary diversity of geography, biology and culture and is blessed with a dynamic, hardworking, loving population, in spite of its constant demonisation in the press, in Washington and in Hollywood popular culture.

May Maloney, who has just returned as an exchange student in the region, the world owes an unacknowledged debt to Colombia:

If Colombia were to be missing from the world then all of Latin America would be suffering from a terrible identity crisis. If Colombia just zipped off the face of the Earth or was never there to begin with then we wouldn’t have ‘Pre-Colombian’ history, or Bolivar’s Pan-American dream. Spain wouldn’t have been able to transport (steal?) the all gold and silver of Bolivia without the port of Cartagena and, moreover, Henry Morgan and Francis Drake (along with all other pirates) would not have entered popular folklore if Santa Marta and Cartagena hadn’t been there to be sacked and razed at will. An obvious gap in the world economy would be left without Colombia—the Panama Canal as we know was once part of Colombia. The international drug economy, largely funded by the US, would have to be relocated to another part of the world and The War on Drugs wouldn’t have arrived at a Plan Colombia. Shakira wouldn’t be bringing her Laundry Service to the world, Miami could crumble to the ground and salsa would only be danced in Cuban circles if Cali hadn’t taught us that you can do it in straight lines. And worst of all for most Melbournians here in the South we wouldn’t be sipping at out ‘Italian’ coffee!

Sing as the birds do

The recent conflict between Ecuador, Colombia and Venezuela has awakened the ghosts of Bolívar. Chavez is seeking to exhume the remains of Bolivar from his crypt in Caracas in order to discover if he was poisoned by the reactionary forces who then went on to rule Colombia.

Meanwhile, among the FARC guerrillas killed by Colombian forces in Ecuador was the folk singer Julian Conrado, who composed revolutionary songs in the traditional vallenato style, music of troubadours from the valley in north-east Colombia. One of his famous songs was El Canto

When you are going to sing

sing as the birds do

it has to turn out beautiful because it is done free of charge …

he who would pay for happiness,

no happiness will find.

The idea of Colombia is a world without value. Travelling through El Dorado to FARC we experience its sublime imagination and fraught reality. And along the way, we might glimpse a truth about the capitalist empire.

Next, southern Italy…

[1] Heide King ‘Gold in Ancient America’ The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 2002, 59: 4, pp. 5-55

[2] Eduardo Galeano Memory of Fire: II Faces & Masks (trans. Cedric Belfrage) New York: Pantheon, 1987 (orig. 1984), p. 138

To consider the idea of South as a ‘zero’ in the capitalist economy, it may be worth looking at its discovery in mathematics. As far as I know, it was the culture of Andalusia in southern Spain where the concept of zero was developed. But I can see a problem ahead: while zero might be very important in the grounding of cardinal numbers, what does it mean for the zero itself? Does this mean that South does not exist?