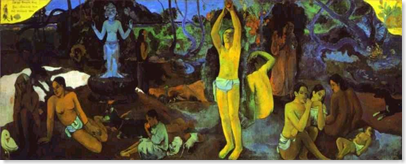

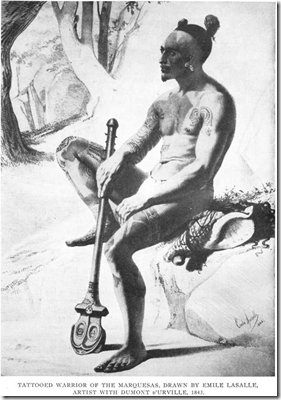

Inspired by Bougainville’s accounts of Tahiti, Jules Sébastien César Dumont d’Urville sought out a mission to explore the south. His first commission was in the Aegean, where he ‘discovered’ the Venus de Milo. In 1822 he was part of an expedition south, when it was still considered possible that France might recover some its recent losses with the acquisition of New South Wales. In his second voyage south, 1826-9, he studied the Pacific peoples and developed the distinction between Micronesia and Melanesia. Finally, in 1837 he was charged with the mission of reaching the magnetic south pole.

Inspired by Bougainville’s accounts of Tahiti, Jules Sébastien César Dumont d’Urville sought out a mission to explore the south. His first commission was in the Aegean, where he ‘discovered’ the Venus de Milo. In 1822 he was part of an expedition south, when it was still considered possible that France might recover some its recent losses with the acquisition of New South Wales. In his second voyage south, 1826-9, he studied the Pacific peoples and developed the distinction between Micronesia and Melanesia. Finally, in 1837 he was charged with the mission of reaching the magnetic south pole.

Dumont d’Urville was a keen scholar of Pacific cultures. He added Polynesian dialects to his wide range of languages, including Latin and Greek, English, German, Italian, Russian, Chinese and Hebrew. He died in a tragic train disaster with his family in 1842. After this death, a manuscript was discovered titled Les Zélandais: Histoire Australienne. He had decided against publishing this semi-fictional account of Maori life during his lifetime in case it threw doubt on his scientific writings.

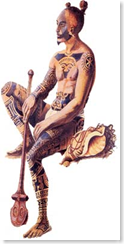

Les Zélandais tells the story of the enlightened chief Moudi, who had been civilised by the influence of a virtuous Pakeha. Moudi’s rival, the barbarous chief Chongui, craves the Pakeha’s beautiful daughter Kadima and eventually forces her to marry him. They have a son, Taniwa, who resists his father’s brutal ways. Chongui sends Taniwa to Sydney in order to obtain fire arms. On his way back, Taniwa is shipwrecked, and eventually brought into Moudi’s kingdom as a captured slave, called Koroké. He soon proves his worth as a warrior and then falls in love with Moudi’s daughter Marama. Moudi eventually acknowledges Koroké’s virtue as a son-in-law, but is puzzled at the lack of knowledge of his family. Eventually Chongui wages successful campaign and takes Taniwa and Marama as captives. But Taniwa escapes and joins Moudi in a final battle against Chongui, at the climax of which the missionaries appear to instill peace and Taniwa is united with Marama.

The novel is based on the understanding that civilisation is not exclusive to Europeans. Even in the most savage cultures, such as Maori, it is possible to find individuals able to recognise the higher values of reason, godliness and charity. While seemingly favourable to the Maori as a redeemable people, Dumont is opposed to the concept of ‘noble savage’. Dumont subscribes to a more Hobbesian view of nature:

O happy Civilisation, fruit of the spirit’s meditations, fecund mother of enjoyment and bliss. Through you alone, roaming man of long ago, at the mercy of his passions, left his forests, gathered in groups and founded those superb cities which are evidence of his power and superiority among the beings of creation… In vain, a few jaundiced philosophes, a few morose critics have tried to deny your excellence and to defend an alleged state of nature which existed only in their disturbed minds. That state of nature is, in reality, only a state of debasement in which man is barely distinguishable from the beasts which surround him, and these same melancholy reformers would themselves blush at being taken back to that state. (p.84)

Dumont’s elevation of the Maori is made possible partly by the denigration of the Australian Aborigine. While in Sydney, Taniwa hears of the hopeless state of native Australians:

Dumont’s elevation of the Maori is made possible partly by the denigration of the Australian Aborigine. While in Sydney, Taniwa hears of the hopeless state of native Australians:

‘this, my dear Taniwa, no more than thirty years ago was nothing but a vast, wild desert. Its inhabitants amounted to the birds in the air, the animals of the forests and a handful of those pathetic human beings whom you see going along our streets sometimes, almost naked, hideous and incapable of applying themselves to any kind of work or any kind of trade.’ (p. 127)

But in taking Maoris as his central characters, Dumont can’t seem to help using their position to pose questions about European culture. Taniwa is puzzled by the spiritless life of the people he observes in London:

‘I would never finish if I tried to report all their stupid customs, all their absurd practices which I have witnessed in quarters which pride themselves on being so enlightened. In short, where those people are concerned, their time is to contrived that every moment of their lives is devoted to imaginary duties and puerile offices, and it leaves them no time to devote to noble reflections of the spirit and to sublime and profound meditations.’ (p. 126)

Dumont’s more conservative position sees the South as a confirmation of European ideals. The benefits of civilisation among the Maori demonstrates the power of Western morality. To achieve civilisation, barbaric traditions have to be disowned. Yet, there is still something remaining in the Maori life that has a spiritual force often missing from the business of empire (particularly British).

Quotes taken from J.S.C. Dumont d’Urville The New Zealanders: A Story Of Austral Lands; (trans. Carol Legge) Wellington: Victoria University Press, 1992