If I had a mother,

Oh Time, leave me alone.

She would offer me food when she ate herself,

Oh Time, leave me alone.

It’s only the gods who know,

Oh Time, leave me alone.

She would say, ‘Here you are my child’.

Patrick Chakaipa[1]

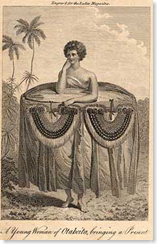

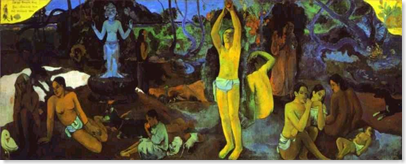

Now we take a sideways leap from the South Pacific to Southern Africa. Both parts of the world have evoked lost worlds and so lent themselves to Western primitivism. These romantic visions mask the often violent political realities of colonisation. But while Tahiti has retained its commodified tourist value, Zimbabwe has become symbolic of all that can go wrong in the South. Is the South inherently less civilised?

The history of Zimbabwe reflects a violent opposition between north and south. Once a thriving empire in its own right, Zimbabwe was crushed by northern colonists and is still yet to recover.

The name Zimbabwe comes from the phrase, dzimba dza mabwe, which means ‘house of stone’. The legendary city of stone known today as Great Zimbabwe has been carbon dated by western methods back to approximately 600 AD. From the thirteenth century, the Maputa Empire traded gold along the Indian Ocean coast, in exchange for goods such as chinaware and Gujarat textiles. In the late 15th century, the empire split into two parts, Changamire in the south (including Great Zimbabwe) and Mwanamutapa in the north. Arabs still populated the trading towns.[2]

The name Zimbabwe comes from the phrase, dzimba dza mabwe, which means ‘house of stone’. The legendary city of stone known today as Great Zimbabwe has been carbon dated by western methods back to approximately 600 AD. From the thirteenth century, the Maputa Empire traded gold along the Indian Ocean coast, in exchange for goods such as chinaware and Gujarat textiles. In the late 15th century, the empire split into two parts, Changamire in the south (including Great Zimbabwe) and Mwanamutapa in the north. Arabs still populated the trading towns.[2]

Then in the early 16th century, Portuguese traders began to arrive via Mozambique. In response, Swahili traders began to re-direct trade away from Portuguese dominated ports through alternative routes north. This began the decline of the Maputa Empire. Eventually, the Ndebele, fleeing the Zulu king Shaka, invaded and established their empire of Matabeleland.

The British arrived in 1880s with Cecil Rhodes’ British South Africa Company. With intimations of the apartheid to come, Rhodes announced in 1887 that ‘the native is to be treated as a child and denied the franchise’

The British arrived in 1880s with Cecil Rhodes’ British South Africa Company. With intimations of the apartheid to come, Rhodes announced in 1887 that ‘the native is to be treated as a child and denied the franchise’

Zimbabwe was a special prize for Rhodes. He subscribed to the myth of the lost tribe of Israel in which the South is seen to contain remnants of Biblical stories. The legendary city of Ophir, the source of King Solomon’s wealth, was presumed to be that of Great Zimbabwe. The quest for biblical wealth became the subject of the novel King Solomon’s Mine by Ryder Haggard.

After having appropriated the Promised Land for Britain, Cecil Rhodes was given a burial that reflected both black and white cultures.[3] His body was carried north by train along his own railway in Bechuanaland (called by Rhodes ‘the Suez of the South’). The body of Rhodes was placed immediately after the engine, ‘so that even in death the great leader still led the way northward’. He was eventually buried in the Matopo hills, a traditional manner signifying his status as a deity of the land. In his will and testament, Rhodes proclaimed a universal Anglo-Saxon world government that would reunite Europe and the USA.

Rhodes’ colleague Lord Baden-Powell pursued the theatre of empire in Rhodesia during the Second Matabele War, when he established the art of scoutcraft to be taught to young boys. It was here that he fashioned the fleur de-lis as the emblem of his movement, so that the boys would always know the way north, no matter how far away they were from England.

Rhodes’ land eventually became Rhodesia, notorious for the apartheid rule of Ian Smith. In 1950, Doris Lessing’s first novel, the Grass is Singing, evoked the hatred fostered between black and white:

When old settlers say ‘One has to understand the country ‘, what they mean is, ‘You have to get used to our ideas about the native.’…

When it came to the point, one never had contact with natives, except in the master-servant relationship. One never knew them in their own lives, as human beings. A few months, and these sensitive, decent young men had coarsened to suit the hard, arid, sun-drenched country they had come to; they had grown a new manner to match their thickened sunburnt limbs and toughened bodies.[4]

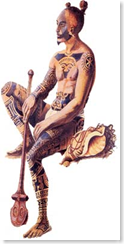

In the midst of this cold regime there were attempts to celebrate Shona culture. In 1966, the free-spirited Frank McEwen arrived from Paris where he brought a passion for primitivism to his new position as Director of the Art Gallery of Rhodesia. Seeking to engage the local culture, McEwen encouraged some museum guards to start carving soapstone and then started exhibiting their dreamlike creations. For

In the midst of this cold regime there were attempts to celebrate Shona culture. In 1966, the free-spirited Frank McEwen arrived from Paris where he brought a passion for primitivism to his new position as Director of the Art Gallery of Rhodesia. Seeking to engage the local culture, McEwen encouraged some museum guards to start carving soapstone and then started exhibiting their dreamlike creations. For  McEwen, their ‘adult child art’ drew from the dormant cultures of Great Zimbabwe.[5] Freed of art education, their creations were ‘born directly, locally, from natural elements in the virgin ground’. McEwen organised successful exhibitions of their work in Europe and thriving market for their work ensued.

McEwen, their ‘adult child art’ drew from the dormant cultures of Great Zimbabwe.[5] Freed of art education, their creations were ‘born directly, locally, from natural elements in the virgin ground’. McEwen organised successful exhibitions of their work in Europe and thriving market for their work ensued.

While successful abroad, Shona sculpture is seen as disconnected from the political realities of life in Rhodesia.[6] A new generation of writers sought to depict the tensions between black and white, urban and rural. Charles Mungoshi’s The Setting Sun and the Rolling World reflects changes and separated generations. The father tries to convince his son to work the land, though he knows there is no future there

While successful abroad, Shona sculpture is seen as disconnected from the political realities of life in Rhodesia.[6] A new generation of writers sought to depict the tensions between black and white, urban and rural. Charles Mungoshi’s The Setting Sun and the Rolling World reflects changes and separated generations. The father tries to convince his son to work the land, though he knows there is no future there

The sun was setting slowly, bloody red, blunting and blurring all the objects that had looked sharp in the light of day. Soon a chilly wind would blow over the land and the cold cloudless sky would send down beads of frost like white ants over the unprotected land.[7]

Such divisions also separate writers themselves. Charles William Dambudzo Marechera was widely celebrated when he arrived in Europe brimming with negritude. He would say, ‘If you are a writer for a specific nation or a specific race, then fuck you.’ This nihilism was criticised in turn as an embrace of European modernism and denial of his roots.

Such divisions also separate writers themselves. Charles William Dambudzo Marechera was widely celebrated when he arrived in Europe brimming with negritude. He would say, ‘If you are a writer for a specific nation or a specific race, then fuck you.’ This nihilism was criticised in turn as an embrace of European modernism and denial of his roots.

On the other hand, the playwright Ngugi wa Mirii remained in Africa to pioneer community theatre, particularly in Kenya. Until his recent death in a car accident, he was one of the most revered writers by the ZANU-PF movement.

On the other hand, the playwright Ngugi wa Mirii remained in Africa to pioneer community theatre, particularly in Kenya. Until his recent death in a car accident, he was one of the most revered writers by the ZANU-PF movement.

While deeply divided over allegiances to global north and south, Zimbabwean culture has its own internal bearings. Shona traditions located the realm of the departed in two different regions.[8] Kubashikufwa is the land of ghosts deep underground, while Kwiwi is the land to the East is where the creator resides.

The South itself has particular meaning for the Venda, who journeyed into South Africa.[9] Their trek was accompanied by a drum called Ngowtu-lungundu, seen to play a role similar to the Arc of the Covenant. It was critically important that the drum never touch the ground in their southward journey.

From the West, there are few countries in the world that seem as dysfunctional as Zimbabwe. The dispossession of white farmers and officially condoned violence seems to fulfil the worst prejudices of previous generations. Some allowance needs to be made for the fear and distrust that brewed during apartheid. But the challenge now is find a voice for Zimbabwe beyond fear and pity. The Chinese don’t seem troubled by this, and are happy to get down to business regardless of politics. When will the western world be open again to the words, songs, images and objects that emerge from this historic land?

From the West, there are few countries in the world that seem as dysfunctional as Zimbabwe. The dispossession of white farmers and officially condoned violence seems to fulfil the worst prejudices of previous generations. Some allowance needs to be made for the fear and distrust that brewed during apartheid. But the challenge now is find a voice for Zimbabwe beyond fear and pity. The Chinese don’t seem troubled by this, and are happy to get down to business regardless of politics. When will the western world be open again to the words, songs, images and objects that emerge from this historic land?

The idea of South in Zimbabwe begins with a mythical lost world, which then unravels to a hell of violence and misery. Can we see beyond this idea to find a Zimbabwe of the future?

Notes

Thanks to David Jamali for his advice and encouragement. As the Zimbabwean proverb goes, ‘An elephant’s tusks are never too heavy for it’.

Next: Uruguay

[1] G. P. Kahari ‘Tradition, and Innovation in Shona Literature: Chakaipa’s Karikoga Gumiremiseve’ Zambezia , 2: 2, pp. 47-54

[2] Randall L. Pouwels ‘The Medieval Foundations of East African Islam’ The International Journal of African Historical Studies (1978) 11: 2, pp. 201-226

[3] Terence Ranger ‘Taking Hold of the Land: Holy Places and Pilgrimages in Twentieth-Century Zimbabwe’ Past and Present (1987) 117, pp. 158-194

[4] Doris Lessing The Grass is Singing Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1961 (orig. 1950), pp. 18-19

[5] Frank McEwen ‘Shona Art Today’ African Arts (1972) 5: 4, pp. 8-11

[6] Carole Pearce ‘The Myth of ‘Shona Sculpture” Zambezia (1993) 20: 107, pp. 85-103

[7] Charles Mungoshi The Setting Sun And The Rolling World : Heinemann International, 1989, p. 93

[8] Denys Shropshire ‘The Bantu Conception of the Supra-Mundane World’ Journal of the Royal African Society 1931, 30: 118, pp. 58-68

[9] A. G. Schutte ‘Mwali in Venda: Some Observations on the Significance of the High God in Venda History’ Journal of Religion in Africa Vol. 9, Fasc. 2. (1978), pp. 109-122.

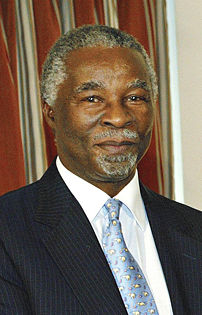

On 21 September, the South African President Thabo Mbeki addressed the nation with the news of his resignation. In a well-discipline speech, he maintained his loyalty as a cadre of the movement and promoted the values of the ANC.

On 21 September, the South African President Thabo Mbeki addressed the nation with the news of his resignation. In a well-discipline speech, he maintained his loyalty as a cadre of the movement and promoted the values of the ANC.