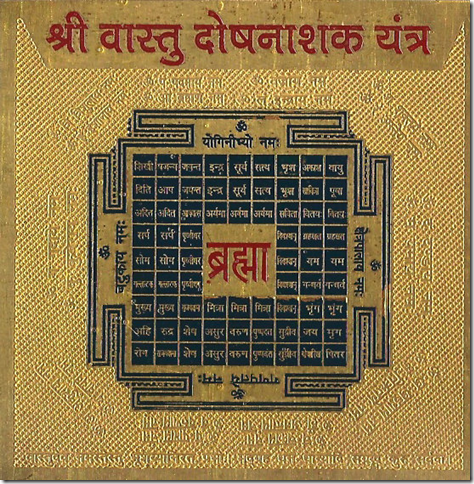

Yantras are square charms whose power is based on words and diagrams. The above yantra was obtained from a market in Ahmedabad, India and contains the principles of India geomancy on which much architecture is based. Vastu Shastra gives particular meaning to the cardinal points. In the Vastu Purusha Mandala, the earth is represented by a square. In this case, the direction on top is east. The morning sun is considered especially powerful. While North is ruled by Kubera, the god of wealth, South is governed by Yama, or death.

Yantras are square charms whose power is based on words and diagrams. The above yantra was obtained from a market in Ahmedabad, India and contains the principles of India geomancy on which much architecture is based. Vastu Shastra gives particular meaning to the cardinal points. In the Vastu Purusha Mandala, the earth is represented by a square. In this case, the direction on top is east. The morning sun is considered especially powerful. While North is ruled by Kubera, the god of wealth, South is governed by Yama, or death.

From heresy to beauty products–the idea of South in France

It is tempting to position the South as a victim of the North. Certainly, the conflict between the French North and South appears to be a story of ruthless oppressor that violently subjugates a peace-loving and tolerant victim. Is that necessarily so? Whichever way, French history straddles a cultural fault-line that continues to move in opposing directions.

France contains at least two nations. While the north was populated by Franks from Germany, the south was a separate entity ruled by Visigoths in the Middle Ages. They were more closely connected laterally with the Catalans than vertically with the Franks. During its independent history, the South, known as Occitania, was a site of resistance to imperial rule.

Their first form of Christianity was Arianism, which taught that God came before Jesus. Around the tenth century, an interest in ‘courtly love’ emerged under the influence of poetry from Andalusia. The word “troubadour” was derived from an Arabic root ta-ra-ba meaning “to be transported with joy and delight”. The literary genre of ‘chanson de geste’ emerged celebrating refinement of taste in contract to the tales of war and heroic deeds prevalent in the north.

At the same time, the religion of the Cathars developed, which denigrated earthly life and adopted values of simplicity and abstinence. In 1208, a Papal legate was assassinated in Saint-Gilles which prompted the Franks in support of Rome to cleanse the South of heresy. The Albigensian crusade led by Simon de Monfort became legendary for its brutality. In 1209 the town of Beziers was sacked and none of the population was spared, even those who sought refuge in the church. When the commander was asked by a Crusader how to tell Catholics from Cathars once they had taken the city, the abbot supposedly replied, Neca eos omnes. Deus suos agnoscet, “Kill them all, God will know His own.” The second crusade against the South involved the siege of Montségur (Montsalvat) during which the inquisition was first established.

The successful completion of the crusade led to the Frankish domination of the South and the status of France as a unified country. Nonetheless, the South continued to be a source of suspicion, characterised as stubborn and greedy. During the reformation, it contained Protestant strongholds. As administration became more centralised around Paris, French was enforced as the language of administrations.

From the Revolution, the South was identified as a source of political change. Some autonomy was restored to the Midi, as it was now called. In the nineteenth century, writers such as Augustin Thierry and Michelet celebrated the South as a source of democracy. In 1854 Frédéric Mistral founded the Félibrige, dedicated to supporting Occitan literature, which gradually shifted to support for the Catholic Right. Inspired by his Nobel Prize in 1904, the Chilean poet Lucila Godoy Alcayaga changed her name to Gabriela Mistral. The mystical legend of Cathars was established by Napoléon Peyrat with the 1871 publication Histoire des Albigeois. But at the same time, there was pressure to standardise French under la Vergonha (the shaming), which prohibited the teaching of Occitan in schools. In reaction, the youth movement

Hartèra emerged to promote Occitan, as one of its posters says:

To hell with the shame…

Our patois is a language: Occitan;

Our South is a country: Occitania;

Our folklore is a culture.

We want respect for our difference.

Share, mix, walk!!

During the 1930s, there were attempts to identify the Cathars as ancestors of the Nazis, particularly through the romantic myth of Montsalvat. However, during Second World War, the area of France not occupied by Germans corresponded to that of Occitania. In 1940, editors of Cahiers du Sud, including Simone Weil and Louis Aragon called a gathering in Marseille to found a community of tolerance. As Weil said at the time, ‘Catharism was the last living expression in Europe of pre-Roman antiquity. It is from this thinking that Christianity descends; but the Gnostics, Manicheans and Cathars seem to be the only ones that remained faithful to it.’ After the war, the South became a site of creative experiment. In 1946, the Dada poet Tristan Tzara founded the Institut d’Etudes Occitanes in Toulouse.

Popular interest developed in 1960 with a two-part television series Les Cathares, drawing on Peyrat’s romantic history. The South became an issue in the revolutionary movement of May 1968

Now the South has become a significant luxury brand, associated with the region of Provencal in cuisine and home goods. Olivier Baussan founded the company l’Occitane, ‘L’OCCITANE has drawn inspiration from Mediterranean art de vivre and traditional Provencal techniques to create natural beauty products devoted to well-being and the pleasure of delighting and caring for oneself.’ This company has now extended its southern taste to other countries. The brand L’Occitane do Brasil expresses the authenticity of a first natural sun care line made exclusively in Brazil.

Now the South has become a significant luxury brand, associated with the region of Provencal in cuisine and home goods. Olivier Baussan founded the company l’Occitane, ‘L’OCCITANE has drawn inspiration from Mediterranean art de vivre and traditional Provencal techniques to create natural beauty products devoted to well-being and the pleasure of delighting and caring for oneself.’ This company has now extended its southern taste to other countries. The brand L’Occitane do Brasil expresses the authenticity of a first natural sun care line made exclusively in Brazil.

Part of the mythology of L’Occitane revolves around the ‘everlasting’ flower immortelle, the source of eternal youth.

Meanwhile, the flower has become a rallying point for revival of Occitan culture. In 1978, the band Nadau composed the song L’immortèla (The Edelweiss) which tells of the flower of love and the mountain journeys of the southern people,

Up we’ll walk, Little Peter, to the edelweiss

Up we’ll walk, Little Peter, until we find that place!

Occitania follows a familiar path in Europe, where civilisations known for their tolerance and poetry fall victim to the northern military regimes. This internal colonisation then provides the rehearsal for the subjugation of peoples beyond. Once the target of heresy has shifted to the colonies, then the internal other becomes a subject of nostalgia and commodification.

Rather than a single identity, countries like France seem constituted by a dialogue between opposing halves. While the heretic South helps to sharpen the values of the North, the brutality of the North conjures the idea of a sensual and tolerant South.

And if I ever lose my north and south…

Moonshadow is considered one of Cat Stevens greatest songs and his personal favourite of that period. It imagines the loss of body parts as a form of liberation.

One curious verse talks about the loss of teeth:

And if I ever lose my mouth

All my teeth, north and south

Yes, if I ever lose my mouth

Oh if, I won’t have to talk..

So what is ‘north and south’ in relation to teeth. The obvious reference seems to be upper and lower teeth. Why?

Well, it helps the rhythm of the song and establishes the rhyme very nicely. But at the same time it does highlight the perverseness of verticalism. There seems no direct link between the upper teeth and north, other than via a modern convention to orient maps in books and on walls with north at the top. The personal is the cartographical.

Oh, I’m bein’ followed by a moonshadow, moonshadow, moonshadow

Leapin and hoppin’ on a moonshadow, moonshadow, moonshadow

John Stanley Martin – Australia as an Iceland of the south

One way of reading an antipodean country like Australia is through the lens of its symmetrical opposites. For many, Australia has been compared to Nordic countries. One of Australia’s leading Nordicists, John Stanley Martin, unfortunately passed away this week. Here he talking about the commonality between Australia and Iceland.

John Stanley Martin, descendent of the Eureka rebels, went to Iceland to pursue a degree in Old Norse. He recalls a conversation with Icelandic novelist Sigurdur Nordal, who saw both nations as sharing the challenge of new beginnings:

John Stanley Martin, descendent of the Eureka rebels, went to Iceland to pursue a degree in Old Norse. He recalls a conversation with Icelandic novelist Sigurdur Nordal, who saw both nations as sharing the challenge of new beginnings:

As an Australian you understand Iceland better than the Europeans do, because we are Europe’s first colony. We are the first time they came. Every time there was a movement in Europe, there was always a group before—the Celts moving in, the Germanics moving in—and there would be an amalgam of the cultures… In Norway, from where they came, it was limited resources, someone gets more and someone gets less. Come to Iceland and it’s a free for all, grabbing land, so you don’t respect the environment in the same way any more.[i]

[i] John Stanley Martin, interview, 16 February 2001.

Why ‘Up in the Air’ should be grounded

New critique or old myth?

You could be forgiven for thinking that the recently released Up in the Air heralds a new wave of American films that reflect the real social realities of America exposed by the Global Financial Crisis.

‘ target=_blank>Rolling Stone claims that ‘Up in the Air is a defining movie for these perilous times’ and gives a ‘bravo’ to its exposé corporate cynicism. The ABC At the Movies gives the film top rating – ‘It is part of the reality of contemporary economic life in America, as opposed to this totally superficial life that he’s living.’

But do we see any change in the key values that lead to the piracy on Wall Street. Take some key features of the film:

- The young woman who challenges the elder male is shown to be an emotional child needing his assistance

- The world is nothing but the United States of America and the key characters (apart from those being sacked) are all white Anglos

- There is not one reference to the carbon emissions generated by jet travel

- The human ‘shark’ who is employed to do the dirty work by faceless companies is revealed to be warm and responsible person compared to the alternative of online retrenchments

- The humble mid-Western couple ‘grounded’ by poverty are gifted a round the world flight by the generous corporate brother (the meek will orbit the earth)

- It celebrates the verticalist fantasy that the world above is exempt from the realities of what lies below

Up in the Air is an attempt to maintain ‘business as usual’ in a culture that is destroying itself and the world through an unbridled capitalism. Just when reality seemed to expose the irresponsibility at the heart of this system, Hollywood coopts the anti-corporate narrative in order to reinforce the very world that created the problem.

Don’t board this flight. I have a premonition that this plane will not arrive at its advertised destination.