Sicily has long been a place for imagining the wider world.

Sicily has long been a place for imagining the wider world.

In 3rd century BC, Archimedes developed the magic of levers to the point where he could speculate, ‘Give me a place to stand on, and I will move the Earth.’

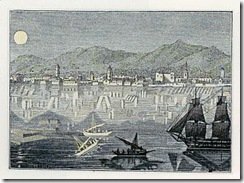

In 12th century Palermo, the court of King Roger II brought together the finest scholars of all religions. Under his patronage, the Arab philosopher Al-Adrisi created an atlas that represented the height of knowledge about the world. Kitab Nuzhat al-Mushtaq fi’khtirdq al-Afaq (‘the delight of the yearner for the piercing of the horizons’) incorporated knowledge of Africa, Europe and Asia. Besides the absence of the Americas and Oceania, the major difference was the orientation of South. South was placed on top, rather would become the convention.

Sicily was a theatre for the struggle to define Europe. Initially part of Greater Greece, Sicily has been alternatively part of the Phoenician, Roman, Byzantine, Muslim, Norman and Spanish empires. The French historian Jules Michelet saw the Punic Wars fought on its soil as a fateful battle between the Indo-Germanic and Semitic families of nations: the victory of the former enabled the West to emerge.

As Goethe witnessed on arriving in 1787, ‘Sicily points me toward Asia and Africa, and it is no trivial thing to stand in person on the remarkable spot that had been the focus of so much of the world’s history.’ For northerners, Sicily was an opportunity to clarify the cultural superiority of the West. In 1771, Baron Hermann von Riedesel noted in Sicily traits of ‘effeminacy, voluptuousness, and cunning, which is found to increase in more southerly countries’.

For many writers, this difference characterised Italy as a whole. John Ruskin’s essay on the Gothic begins with a panoramic journey from north to south, contrasting the ‘prickly independence ‘ represented in Northern ornament against the priestly mystification of Southern culture. The experience of the Grand Tour, from Dover to Naples, testified to the opposition between the sensible North and corrupt South.

For many writers, this difference characterised Italy as a whole. John Ruskin’s essay on the Gothic begins with a panoramic journey from north to south, contrasting the ‘prickly independence ‘ represented in Northern ornament against the priestly mystification of Southern culture. The experience of the Grand Tour, from Dover to Naples, testified to the opposition between the sensible North and corrupt South.

This European fault line was internalised within Italy itself. Rather than contest this prejudice, the response was to scapegoat the Southern region. In 1898, a Sicilian criminologist Aliredo Niceforo published L’Italia barbara contemporanea (Contemporary barbarous Italy) which argued a phrenological difference between Northern and Southern Italians, based on the contrast between Aryan and Mediterranean types. The Northerner had greater capacity for social organisation, whereas the Southerner possessed a more perverse genius. Niceforo’s aim was to find ways of civilising the South.

The eventual unification of Italy began in Sicily, with the successful campaign of Giuseppe Garibaldi in 1860. Garibaldi developed his revolutionary skills in Latin America. He had been head of the Uruguay Navy and joined in marriage to the valiant soldier, the Brazilian Ana Ribeiro da Silva. Know as the Mezzogiorno after the hot midday sun, Garibaldi saw the Kingdom of Two Sicilies as critical to the future constitution of the Italian nation.

The eventual unification of Italy began in Sicily, with the successful campaign of Giuseppe Garibaldi in 1860. Garibaldi developed his revolutionary skills in Latin America. He had been head of the Uruguay Navy and joined in marriage to the valiant soldier, the Brazilian Ana Ribeiro da Silva. Know as the Mezzogiorno after the hot midday sun, Garibaldi saw the Kingdom of Two Sicilies as critical to the future constitution of the Italian nation.

Following Garibaldi’s campaign, a movement emerged to challenge the cultural prejudice towards the South. The school of meridionalismo included writings about the dire poverty of the south, such as Pasquale Villari’s Southern Letters (1875) which focused on the scandal of Neapolitan life. Rather than point the blame at the moral character of Southerners, writers like Villari accused the Southern elites of having little regard for their own people.

The communist Gramsci placed this on the international stage with his essay the Southern Question (1926), written in prison. Gramsci tried to create solidarity between Turin workers and Southern peasants. He argued that the lowly status of Southerners is due to bourgeois propagandists, who argue that ‘if the South is backward, the fault does not lie with the capitalist system or with any other historical cause, but with Nature.’

Elements of post-war Italian culture proved more sympathetic to the South. In cinema, Neorealism emphasised the life of ordinary people. Visconti’s Rocco and his Brothers (1960) depicted the plight of Southern immigrants in the industrial Milan. In visual arts, Arte Povera introduced by Germano Celant in 1967 also provided a space for representing the pre-Industrial Italy in the use of found materials.

Elements of post-war Italian culture proved more sympathetic to the South. In cinema, Neorealism emphasised the life of ordinary people. Visconti’s Rocco and his Brothers (1960) depicted the plight of Southern immigrants in the industrial Milan. In visual arts, Arte Povera introduced by Germano Celant in 1967 also provided a space for representing the pre-Industrial Italy in the use of found materials.

While there was a place for the South in the culture of the North, the dominant response in the South itself was to isolate itself from the North. Sicilianismo is a term use to describe a stubborn resistance to innovation, associated with a suspicion of more powerful neighbours. It manifests itself most famously in the mafia, of Arabic origin, which operates as a secret hierarchy in opposition to the state.

In the 20th century, the mafia put Sicily on the global stage. Hollywood directors of Italian descent such as Martin Scorsese drew on the Sicilian experience to depict the lives of immigrants in America. In the Godfather series, Francis Ford Coppola used Sicily as a narrative kernel to underpin the violence of the mafia in the US. From Sicily comes the code of honour on which drives revenge and sacrifice.

In the 20th century, the mafia put Sicily on the global stage. Hollywood directors of Italian descent such as Martin Scorsese drew on the Sicilian experience to depict the lives of immigrants in America. In the Godfather series, Francis Ford Coppola used Sicily as a narrative kernel to underpin the violence of the mafia in the US. From Sicily comes the code of honour on which drives revenge and sacrifice.

It’s been noted that the Godfather series presents a distorted view of Sicilian life as exclusively patriarchal. The normal intense relationship between the Sicilian mother and son is completely absent. It could be argued that the Godfather films address a contradiction in American culture, between the modernising challenge to hierarchy and the celebration of male power in military and sporting life. Rather than locating patriarchy in the early fathers of the American Revolution, it is symbolically situated in far away Sicily. Al Pacino becomes the imaginary hero for ambitious men in board rooms and hard-headed sales meetings.

Eventually the modernising wins. The Sopranos series had an ironic relationship to patriarchy. The second season episode ‘Commeditori’ starts with the gang excited by their forthcoming trip to Naples to make a deal in stolen cars. They discuss their plans while trying to watch a bootleg copy of Godfather II. When they eventually arrive in the Italian South, the gap between the two cultures proves insurmountable and Tony has difficulties dealing with the woman who is in charge of local mafia business. Meanwhile, at home, the wives are carving up their husbands personalities.

Eventually the modernising wins. The Sopranos series had an ironic relationship to patriarchy. The second season episode ‘Commeditori’ starts with the gang excited by their forthcoming trip to Naples to make a deal in stolen cars. They discuss their plans while trying to watch a bootleg copy of Godfather II. When they eventually arrive in the Italian South, the gap between the two cultures proves insurmountable and Tony has difficulties dealing with the woman who is in charge of local mafia business. Meanwhile, at home, the wives are carving up their husbands personalities.

In modern Italy, the north-south divide has been exacerbated by the rise of the Lega Nord, representing the interests of northern Italians from regions such as Piedmont and Lombardy. They consider the South to be a drain on the national resources. Their catchcry has been ‘Africa starts at Rome.’ The Berlusconi phenomenon is partly due to the support of the Lega Nord, though the target of Southern scapegoating has changed.

In the Berlusconi’s recent re-election, Lega Nord’s campaigned on a platform of anti-immigration. The spotlight is on the island of Lampedusa where refugees from Libya and Ghana arrive, eventually to find piece work on the farms, harvesting tomatoes for export to countries like Australia.

It seems that the only way to move beyond the North-South divide is to shift it somewhere else. Sicily no longer seems to far South as Libya. But there is an alchemy in Italian culture that can occasionally reverses this effect.

Recent attempts to build a bridge between the Sicily and the rest of Italy have been abandoned. The Straits of Messina continue to keep the two cultures different. These waters are also the scene for the mysterious Fata Morgana, an illusion of separate floating worlds, sometimes upside down.

Recent attempts to build a bridge between the Sicily and the rest of Italy have been abandoned. The Straits of Messina continue to keep the two cultures different. These waters are also the scene for the mysterious Fata Morgana, an illusion of separate floating worlds, sometimes upside down.

The South can look back.

References

- John A. Agnew Place And Politics In Modern Italy University of Chicago Press, 2002

- Geoff Andrews Not a normal country: Italy after Berlusconi London: Pluto Press, 2006

- Tommaso Astarita Between Salt Water and Holy Water: A History of Southern Italy W. W. Norton & Company, 2006

- Timothy Brennan ‘Literary Criticism and the Southern Question’ Cultural Critique (1988) 11, pp. 87-114

- Richard Drake ‘Meridionalismo, the Crisis of Liberalism, and the Advent of Marxism in Post-Risorgimento Naples’ The European Literacy (2004) 9: 4, pp. 481-5020

- J.W. Goethe Italian Journey (trans. Robert R. Heitner) New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1994 (orig. 1786)

- Michel Huysseune Modernity And Secession: The Social Sciences And The Political Discourse Of The Lega Nord In Italy Berghahn Books, 2006

- Nelson Moe The View From Vesuvius: Italian Culture And The Southern Question Berkeley and Los Angeles, Calif.: University of California Press, 2002

- Martha P. Nochimson ‘Waddaya Lookin’ at?: Re-Reading the Gangster Genre through “The Sopranos”’ Film Quarterly 2002, 56: 2, pp. 2-13

- John Ruskin Stones of Venice New York: Da Capo Press, 1960 (orig. 1853)

- Fred Gardaphé Re-Inventing Sicily in Italian American Writing and Film MELUS 2003, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 55-71

- See also a film about Gramsci introduced by Edward Said, describing the Middle East as a ‘North-South question’.