Looking from above, we often search for glimpses of north-ness down in the South. Along with the glittering Paris’s and Venices of the South, there are several locations that lay claim to the title ‘Switzerland of the South’. Each identifies with different elements of Switzerland. For Tasmania, it is the picturesque mountain scenery. In the case of New Zealand, it is libertarian values. But the title has seemed particularly apt for a tiny nation wedged between the super-powers of South America.

Uruguay was crowned the ‘Switzerland of South America’ in the first decades of the 20th century. Nature had little to do with this title. It resulted more from the European social democratic system of liberal values and tax laws introduced by President José Batlle y Ordoñez. For a period, Uruguay was blessed by a prosperity ornamented with art deco architecture.

Yet there are less idyllic aspects of Uruguayan history not so visible from high above. Down on the ground, we find a fiercely political contest between conservative and radical forces. In the mid 19th century, a nine year civil war pitched the conservative whites, supported by Argentina and based in provinces, against the liberal reds, supported by European interests and concentrated in Montevideo.

The North took great interest in this battle. The siege of Montevideo was compared by Alexander Dumas to the Trojan War. Giuseppe Garibaldi led the Italian legion in the eventual liberation of the capital. Europe cheered the liberal urban elites in their struggle against the feudal lords.

The political conflict during the 20th century was more internalised. During the 1970s and 1980s, Uruguay experienced a period of military repression which was particularly brutal, even by comparison with its neighbours. At one stage, Uruguay had the highest per capita percentage of political prisoners in the world. Like most other neighbouring countries, Uruguay is now governed by centre-left President, Tabaré Vázquez.

There is much in Uruguayan culture that is unique and different from the North. Unlike its neighbour Argentina, the culture of the African slaves survived to play a key role in defining its national identity. Candombe emerged in Montevideo as a dance performed by Africans in places called ‘tangos’. Today Candombe can be found as a procession of drummers who perform ‘llamadas’ (calls) as they march down streets—slowly to reference their previous life in chains. Competing tribes are distinguished by their own rhythm.

Also associated with carnival is Murga, a form of musical theatre derived originally from Cadiz, Spain. Murga is a play combining songs and recitative performed by a group of brightly dressed men, who sing in harmony to the accompaniment of percussion instruments. The content is often subversive and associated with resistance to previous dictatorships.

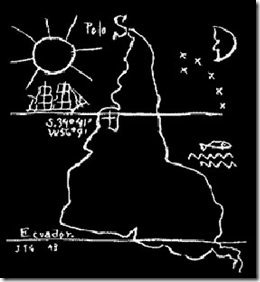

Leading cultural voices of Uruguay have strongly identified with its south-ness. The painter Joaquín Torres García lived in Paris during the 1920s, where he had been part of Pablo Picasso’s circle, and discovered pre-Colombian culture at the Trocadero. He returned in 1934 to establish the Escuela del Sur (School of the South), where he developed a movement unique to the South called ‘Constructive Universalism’. Torres García incorporated pre-Colombian symbols into a Western grid. For Torres Garcia, the South represented the future of art:

I have said School of the South: because, in fact, our North looks South. For us there must not be a North, except in opposition to the South… This correction was necessary; because of it we know where we are.[1]

The essayist Eduardo Hughes Galeano is a voice of conscience for Latin America as a whole. Books such as The Open Veins of Latin America and his three volume series Memory of Fire outline the brutal events that accompanied the emergence of Latin America. Recently in Democracy Now, Galeano described the cultural syndrome of impotence prevalent in the South:

…something condemning you, dooming you to be eternally crippled, because there is a cultural saying and repeating, “You can’t.” You can’t walk with your own legs. You are not able to think with your own head. You cannot feel with your own heart, and so you’re obliged to buy legs, heart, mind, outside as import products. This is our worst enemy…

For Upside Down World, he locates this lack of confidence particularly in Latin America:

All through the first half of the nineteenth century, a Venezuelan called Simón Rodríguez, travelled through the roads of our America, on a mule, challenging the new holders of power: “You,” Simon would cry out, “you who so imitate the Europeans, why don’t you imitate from then what is most important – originality?”

The poet Mario Benedetti is equally famous across Latin America, though his politics is expressed in a more personal language. He began his writing career as a journalist, until his paper Marcha was shut down by the dictatorship. Bendetti was drawn out of Uruguay. Inspired by the 1959 Cuban revolution, he went to live in Paris during the early 1960s, when he wrote Noción de Patria (A Notion of My Country, 1962). This poem opposes imported models of place to the more authentic experience of unfamiliarity:

But now there aren’t any excuses left

Because it all relates back to this place

It always relates back to this place.

Nostalgia seeps out of books

And plants itself under my skin,

And this city that never sleeps,

This country that doesn’t dream,

Quickly becomes the only place

Where the air is mine

The fault is mine

And the sag in the mattress is mine,

And when I extend my arm I’m sure

About the wall I touch, or the emptiness that surrounds me,

And when I look at the sky

Over here, I see clouds, and over there, the Southern Cross

Everybody’s eyes make up my surroundings

And I don’t feel as if I’m on the outside

Now I know that I don’t feel as if I’m on the outside.

Maybe my only notion of my country

Is this urgent desire to say Us

Maybe my only notion of my country

Is this return to the uncertainly itself.[2]

After living in Havana during the late 1960s, Benedetti returned to Montevideo, where he founded a coalition of left-wing groups. Assassination attempts forced him to flee to Spain. Since his return, Benedetti has been a leading voice for the newly confident Latin America. In 2005, Hugo Chavez quoted his poem ‘The South Also Exists’ at the opening of the G-15 Summit:

With its French horn

and its Swedish academy

its American sauce

and its English wrenches

with all its missiles

and its encyclopedias

its star wars

and its opulent viciousness

with all its laurels

the North commands,

but down here

close to the roots

is where memory

no remembrance omits

and there are those

who defy death for

and die for

and thus, all together

work wonders

be it known:

the South also exists.

This performance by Joan Manuel Serrat responds to the vertical position of the South:[3]

New dimensions of Uruguayan culture are still being discovered. A publication by a 19th century anonymous Uruguayan writer has recently been unearthed. The Book of Disengagements is a series of aphorisms in the style of Ferdinand Pessoa, which celebrates non-being. In a very abbreviated form, they reflect the presence in absence where Uruguay seems to find itself:

You are nothing, true; but that nothing already is something.

Notes

Special thanks to Andres Pelaez for his assistance with this entry. Also see Carlos Capelán for a more complex perspective.

[1] Arnulf Becker Lorca ‘Alejandro Álvarez Situated: Subaltern Modernities and Modernisms that Subvert’ Leiden Journal of International Law 2006, 19, pp. 879-930

[2] Mario Benedetti Little Stones at my Window translated by Charles Hatfield, Willimantic: Curbstone Press, 2003